The following is the first chapter from my new book, The Boring Patient. Buy it now:

You can buy it now via CreateSpace (my preference) and Amazon. You can also get the eBook via Amazon (and Amazon Unlimited).

Chapter 1: Getting to Know You

I strive to be the boring patient. In the hospital, or during chemotherapy, I want to be the charming man who only requires a vitals check or a scheduled chemo dose. You don’t want to be interesting in most medical settings. Interesting means complications, and that is bad. I did not originally set out to be a boring patient. I never set out to be a patient at all. I’m a professor, a husband, a father, a speaker, a writer…but a patient? A patient, sick, needing to be cared for, weak? No.

Now don’t get me wrong, I was hardly without my run-ins with the medical profession. I used to say that if it was hard to diagnose, painful, annoying, but not life threatening, then I would have it. Kidney stones? Yup. Digestive issues? You know it.

I remember the faces of the doctors in the emergency room when they told me I had gallstones. My wife had rushed me to the hospital because I was doubled over on the kitchen floor in pain. After many tests and hours the doctors came into my room looking very earnest and told me “gallstones.” I cracked up. Seriously, laughed like a maniac…painful, non-lethal, that’s me. I should take bets on my appendix and tonsils.

It was around 1994 during my doctoral studies that I realized that it was pretty much my brain versus the rest of the meat that made up my body. Ken Robinson[1] puts this beautifully when he describes the structure of America’s education system. He says when you are in kindergarten your whole body is involved in learning…singing and moving. By about second grade we have students sitting in chairs to learn, losing the lower half of the body. As the system continues through middle school, to high school, to college we use less and less of our bodies: hands to write, arms to raise. If you go to the extreme of that system, your Ph.D., you end up inside your head, and slightly to the left. The rest of you body is only used to move you from meeting to meeting.

This meant I didn’t really give my body much thought other than waiting for the next weird thing to happen to it…I mean me. I was (am) fat, balding, and ate like crap (sorry ladies, he’s taken). I’ve had 7 kidney stones with no real explanation as to why or how to avoid them – instead opting to carry around powerful painkillers just in case I had another stone during a transatlantic flight. I had my gall bladder removed, and was one of the lucky 10% of folks that develop “bile malabsorption issues,” that means taking a chalky powder every morning or having to run to the bathroom at 2:30 every afternoon. I have Irritable Bowel Syndrome that means even with the powder there is an excellent chance I will be running for the bathroom at all times of the day anyway if I eat the wrong thing.

By the way, fun fact, know why they call it a syndrome? It means the medical community has no real idea of the cause. It’s like telling the doctor, “Something’s wrong with me, but I don’t know what it is,” and having the doctor say, “Yes, I agree,” and then billing you.

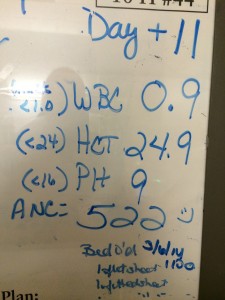

This set of annoying medical interactions is why, in some ways, it was a relief when I was first diagnosed with Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. It was something real. It had a name and a treatment and a plan. It could be made boring. It is a cancer that comes with a built in schedule. Chemo on days 1 and 15, then 15 days off. What was chemo? Sitting in a chair for four hours. The chemo regime, called ABVD (so called after the toxins used: Adriamycin, Bleomycin, Vinblastine, Dacarbazine) is almost 30 years old.

But through the infusions, through the surgeries, through the scans, I learned something very important. I may be the boring patient, but I could never be the passive patient. To be boring is not to be idle, or ignorant, or complacent. The road to my health did not and shall not come from simply following the instructions of a doctor on high. Rather it will come from me learning, and integrating a whole host of talents and expertise.

But I am getting ahead of myself. I should explain a little about this book, and why I am writing it. This book is not about cancer. It is about my response to being diagnosed, living with, and being treated for cancer. That is an important distinction because cancer is not funny. Cancer sucks. Cancer does not teach, cancer does not preach, cancer does not comfort, or inspire, or inform. Cancer kills. How one responds to cancer? That is a completely different matter.

With that out of the way, and before we start with the whole response thing, we should get to know each other. I know I am writing this for myself and my children (when they’re old enough to get all the jokes), and I think it could be useful for others living through a journey with cancer. However, the folks I really want to read this are in the business of delivering health care like doctors, med students, nurses, and medical administrators. So here are a few words for those groups to put them in the right mindset for the book.

Dear Doctors

Hi. I come humbly before you to suggest you need to change. I know that doesn’t sound too humble, and I wouldn’t bother you, but I think the changes I’d like to talk about are very important. I know you’ve done a lot of hard work to get to where you are today. I know the work you do is noble. However, I think your profession is changing and not all in a good way. What’s more many of these changes aren’t in your control.

I say these changes are important not only as a patient, but as a professor and information scientist. I don’t roll out my credentials as a way of sounding important, but more as a cautionary tale. You see I am a tenured full professor at a research university and in the past 5 decades folks like me have gone from the norm in academia to the minority. Have you noticed any discussions recently of calling doctors “health care providers,” and patients “customers?” Have you noticed how much time you spend learning how to enter what you do into a computer system, and less in actually performing medicine? How about this one…have you noticed how as more doctors head to administration they are being replaced not by more doctors, but other “health care providers?” Have you noticed a change in environment that has led to 9 out of 10 doctors recommending folks NOT go into medicine as a profession?[2]

I’ve studied a lot of professional service providers (teachers, professors, librarians) and there are moves afoot across these domains. You call it patient-centered, my colleagues call it user-centered, teachers call it learner-centered, but it comes down to a change in relationship between those you serve and yourself. And it can be great. Instead of seeing patients as a bag of symptoms or as a lawsuit in the making, it is important to see them as people who are ultimately responsible for their own health. That’s easy to say, but it can be hard to make real.

I have also seen all this “centeredness” turn into rampant consumerism. I have seen it turn into attempts to automate people out of jobs. I have seen it turn into deliberate diminishment of status and importance in organizations. We need to avoid that.

Dear Medical Student

Those are my lymph nodes; my eyes are up here. Look I know you are learning a lot, and I know that the vast majority of it is about, well, you know, medicine. That’s very important. It’s why I will always take the time to be poked and prodded by you folks. However, let me be as clear as possible, there is a distinct difference between a car engine and a human patient. That may seem obvious, but it is not always seen in how doctors behave. People, unlike cars, have feelings, fears, opinions, and need to be part of their treatment.

Here’s the good news and the bad news. The good news first. Good research has shown that major innovations in a field come from the field’s newest members. You have the most precious gift of fresh eyes and a new perspective on the problems of medicine. You’ve been raised in a world of greater technology and communications. You’ve been sold the idea of heroic innovators. You can make a huge difference.

Now, the bad news. There is also a fair bit of research that shows that graduate students inherit the behaviors of their mentors and advisors. In some cases, this makes sense; it worked for them and put them in a position of being mentors and advisors. However, see the part I wrote for doctors…the world is changing. I see it from the “information” perspective, but you can no doubt already see it from the medical perspective. It is not just about new treatments and therapies. It is about new organizational structures and economics. Beware when people try to get you to call folks like me customers and not patients. I am not your customer, I am your partner, and you and I are going to have to work together in new ways if I’m going to stay healthy, and if you are going to remain important.

Dear Heroic Noble Inspiring Cancer Survivor

The first line of the first pamphlet I read after my diagnosis of cancer told me I was a survivor. I didn’t have to be cured to be a survivor, I guess I just had to be breathing. This struck me as a pretty low threshold. But as you have probably already found out, there are a ton of stupid metaphors and assumptions around cancer.

Take “fighting cancer”…yeah, that’s what it feels like to lie in a bed asleep for 16 hours straight…fighting. Or, I love it when folks tell me I’m heroic. If anyone was given the choice to take drugs to extend their life wouldn’t they do it? That’s not heroic, it’s common sense. I hope, like me, you have made the brave decision to try not to die.

So what’s in here for you? I hope some comic relief. Seriously, humor has been the best medicine I have gotten – other than, you know, actual medicine (that’s Seth MacFarlane’s joke I stole). You’re going to hear a lot about the importance of a “positive attitude.” Screw that. You have cancer and could die from it. Feel free to cry, scream, piss people off, and flip the bird to God (he can take it). I do have to tell you, however, that gets very tiresome after a while. Tiresome not for everyone else, who cares, but to yourself. So why not confuse everyone and be happy…besides they all have to laugh at your jokes now.

Dear Everyone Else

What I really hope you get out of this is a chance to expect more from those who you work with in your life. Doctors, lawyers, architects, librarians, teachers, engineers, all of these folks are now working in a different world than the age of the almighty experts. The days when you sat quietly and did what some expert told you because they were an expert are gone.

The experts are still here, and expertise is still important. However, the new measure of expertise is not in how well the expert performs their craft, but in how much better that makes you perform. Architects, lawyers, doctors and such are there to make you better, to teach you, to empower you, not simply to service you like a car.

At the very least read my story and laugh – I hope. If you get inspired by it, realize that is your prerogative, but it is not the reason I got cancer.

Notes

[1] http://www.ted.com/talks/ken_robinson_says_schools_kill_creativity

[2] http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2014/04/14/how-being-a-doctor-became-the-most-miserable-profession.html

More on the book at http://rilandpub.wordpress.com/about/the-boring-patient/

Just in time for the holidays, you can now listen to my recent book, The Boring Patient, read by the author as an unabridged audio book (3 hours 17 minutes).

Just in time for the holidays, you can now listen to my recent book, The Boring Patient, read by the author as an unabridged audio book (3 hours 17 minutes).