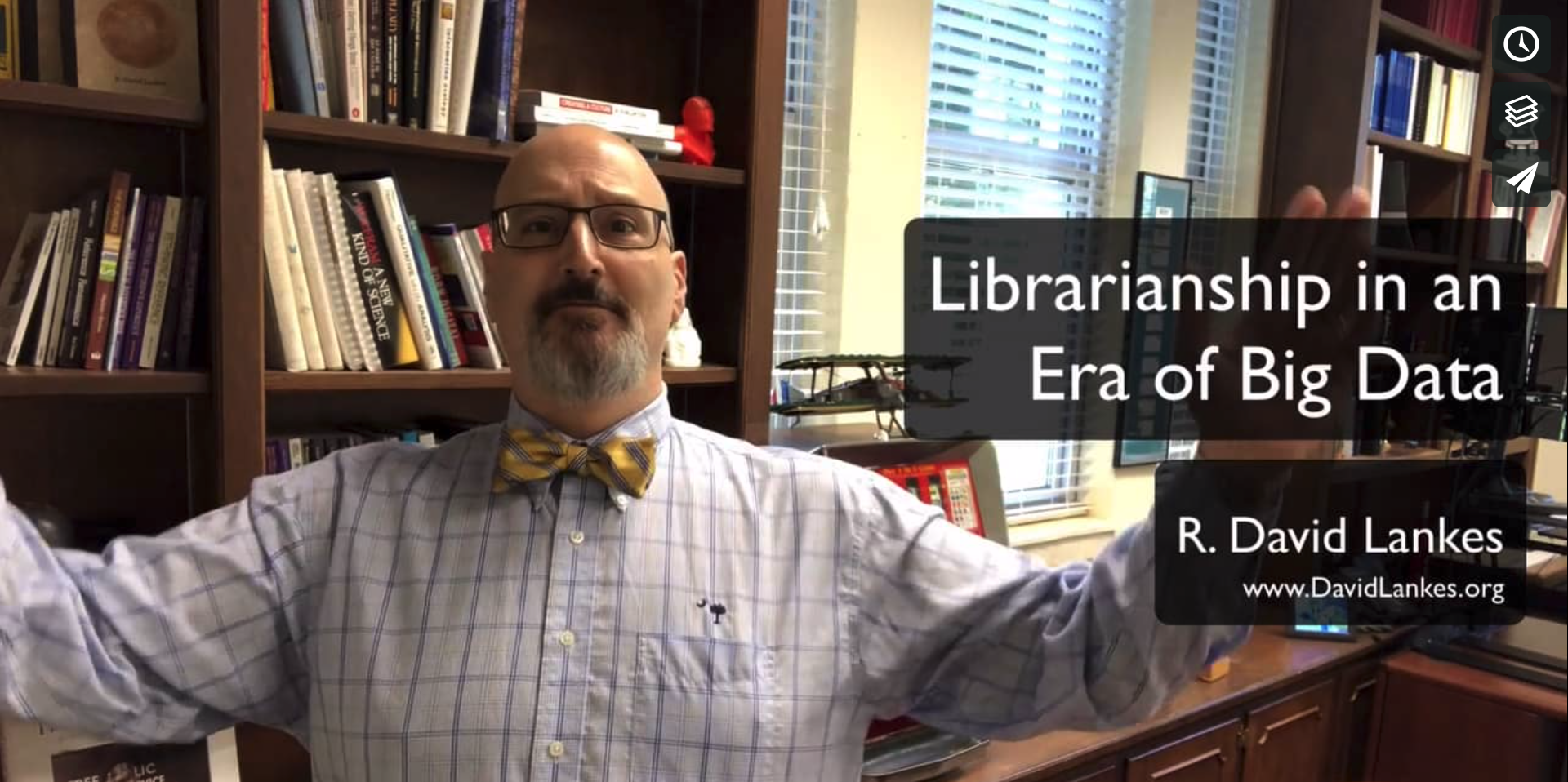

“Librarianship in an Era of Big Data: The Vital Human Touch.” Conference of European National Librarians. Mo i Rana, Norway. (via video conference)

Speech Text: Read Speaker Script

Abstract: In a world of AI and Big Data the values, skills, and mission of librarians is increasingly vital. How do we prepare our professionals to guide and support communities across the EU? How do we ensure the smart citizen is at the center, and in control of the smart city? It is crucial that librarians advocate for issues of privacy and the common good in the midst of a growing market place that transforms users into products. How can librarians increase their value, work with technology giants to shape services, and in the end help our communities make smarter decisions and community members find meaning in their lives.

[This is the script I used for my talk. I’ve also taken the opportunity to add some foot notes and links.]

First, I must begin with an apology to Cecile and the organizers. For weeks they have been asking for slides. I have struggled to put into a concrete form what I want to say to such an important and, frankly, intimidating crowd. I have also spent a year wrestling with cancer and a bone marrow transplant. I don’t say this to get sympathy (maybe a little), but I have found that the experience has given me a new perspective on things that I am still trying to integrate. At once, I am grateful for just about everything, but tend to be less patient with things I feel need changed. And to be clear, as I look out at my home country and across the Atlantic, I see some need for change.

This crystalized for me when preparing for the talk and kept coming into the phrase “memory organizations[1].” If indeed Santayana was right that “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it[2],” then what obligations does that place upon institutions who are charged as memory keepers of nations? I would argue that as stewards of cultural heritage, we are also stewards of society. I would also argue that we must stop serving communities, and start building them.

Our communities, our societies, our cultures are too important to sit on the sidelines and simply observe or collect their output. We must recognize, without the haze of nostalgia, that we are actors in this world and accept a responsibility to work directly with communities of all types to shape a better tomorrow.

Now this could, and should, take many forms. Confronting growing economic disparities, alerting the world to the dangers of xenophobia mixed with nationalism, or confronting the realities of climate crisis. I could talk about the continuous marginalization of whole segments of the population because of race, or class, or sexual preference. Marginalization by society, and indeed, all too often by librarians and the libraries they manage.

Today, however, I would like to use just one societal issue to support a call for national libraries to directly build communities. This incredibly consequential issue often goes unnoticed. It is the dangerous aspects of an increased societal reliance on data-driven algorithms generated by artificial intelligence and machine learning methods.

Before I begin, let me throw out a few caveats and clarifications. The use of data, when appropriately gathered and analyzed is incredibly powerful. Indeed, it underlies most of science. The rise of artificial intelligence, machine learning, and indeed Big Data has unquestionably brought massive benefits to many disciplines. The ability to search through trillions of pages in milliseconds, search across massive number of images, and the ability to automate complex processes have directly benefited librarians. The issue, as I see it, is when we believe that data gathering, analysis, and encoding into algorithms are somehow neutral acts without social costs[3].

In terms of clarifications; I will use the term community a lot. That is often seen as synonymous with towns, or citizens of a city. I use the term more broadly. When I say communities, I mean a group of people joined by some known variable and that share a means of allocating limited resources. A town is indeed a community sharing a common location, and a system of governance that allocates land, taxes, and other resources. A university is a community of scholars, staff, students, and administrators. A community can be a law firm, or a hospital, or a national library.

The other caveat is on the topic of national libraries. I have done some work with national libraries, but much of my relevant experience is working with state libraries here in the US. There is an old joke that once you know one state library, you know…one state library. I don’t pretend to be an expert on European National Libraries. However, from what I’ve seen, this is true of your institutions as well.

Some of you are active in networks with public and academic libraries. In some countries, there are multiple national library agencies. Some actively seek to support business communities[4], others focus on scholarly research. Bottom line – no one set of issues or models will reflect your great variety.

That said, I am reminded of the saying, “every idea is a good idea in libraries, just not in my library.” It is very easy to focus on what differentiates us now and believe that prevents collective action in the future. I hope I can successfully persuade you otherwise

So, with the caveats and clarifications out of the way, my purpose today is to recruit all of you to build a network of proactive librarians around European. I am calling on you to directly support, train, and empower librarians from those working in the most rural public library to those in the most prestigious university. What’s more is that I am asking you to engage in community building to shape a better future. Why? Well, let’s start with a story.

Charles Duhigg, author of “The Power of Habit[5],” tells the story of an angry father who storms into a department store to confront the store manager. It seems that the store had been sending his 16-year-old daughter a huge number of coupons for pregnancy related items: diapers, baby lotion and such. The father asks the manager if the store is trying to encourage the girl to get pregnant? The manager apologizes to the man and assures him the store will stop immediately. A few days later the manager calls the father, only to find that the daughter was indeed pregnant, and the store knew it before she told her father.

What’s remarkable is that the store knew about the pregnancy without the girl ever telling a soul. The store had determined her condition from looking at what products she was buying, activity on a store credit card, and in crunching through huge amounts of data. If we updated this story from a few years ago we could add her search history and online shopping, even her shopping at other physical stores. It is now common practice to use online tracking, wifi connection history, and unique data identifiers to merge data across a person’s entire life.

I am hardly telling you anything new here. Facebook is only the latest business to dominate the headlines with privacy breaches, and hidden data gathering. Most citizens of the EU and the US now live two lives: their own, and one created, often without their knowledge, from the digital debris created through our devices. Add to this increased requirements by governments and businesses alike to be online – to apply for a job, to vote, to receive health care, to listen to music – and we see a world that is moving faster than regulation, and faster than realization by those we seek to serve.

In Toronto, Sidewalk Labs, a subsidiary of Alphabet, Google’s parent company, is working with town planners to redevelop Toronto’s Eastern Waterfront. The story of transforming old industrial areas into gentrified multiuse spaces is nothing new. However, a large part of the controversy in this case comes in the plan to make the new neighborhood a data generator. The plan, according to The Intercept, “includes a centralized identity management system, through which ‘each resident accesses public services’ such as library cards and health care[6].” There has been a large debate over who owns and controls the data generated by that system, and who can profit from it.

Many librarians might look at these examples and claim a sort of ethical high ground. After all, as a profession, we explicitly value privacy. In the US we count it as a core value of the field, and yet we often undermine it. We tell our online patrons that we don’t track their work. And yet their internet provider can indeed track every click they make. Therefore, we are often misleading that patron and giving them a false sense of security. How many libraries set up TOR servers[7]or anonymizing VPN services[8]for our service populations? How often in our licensing of databases or other software do we explicitly forbid the aggregation of user data or the selling of that data? How often do we check on those terms?

Then there is the question of how all of this data is used.

In her book “Weapons of math destruction[9],” Cathy O’Neil documents story after story of data mining and algorithms that have massive effects in people’s lives, even when they show clear biases and faults. For example, an algorithm that led to outstanding teachers being fired. How? O’Neil writes about an outstanding teacher who had proven positive effect on under-performing students– raising their performance and grades significantly. As a reward, the teacher is given a year with honors classes filled with the brightest students in the school. However, the impact a teacher can have on honors students is not nearly as evident as those with students needing a lot of help. After all, top students receiving top marks can’t get better than, well, top marks. So the algorithm saw a teacher that was no longer effective in a classroom, and recommended the teacher be fired. Recommended by a piece of software using criteria that was hidden from teachers, and was assumed to be objective.

Algorithms are now used here in the states to determine health care cost and availability; access to credit for home ownership; suitability of a candidate for a job,; and even how long a person should be in jail.

Yuval Harari refers to this reliance on collectable data and algorithms as Dataism[10]. It is the result of computing power combined with machine learning and the wide availability of constantly connected devices like our phones. It is the belief that if you gather enough data on a person or situation, you can accurately represent that person or situation and predict an outcome.

It often also comes with some very dubious, and downright dangerous assumptions. Assumptions such as algorithms are objective, and that data collection is somehow a neutral act. Or even, that everything can be represented in a quantitative way – including, by the way, culture[11]. And before I make you wonder what any of this has to do with the work of libraries, or think I’m letting our profession off the hook, I have to say that librarians have suffered from some of the same dubious assumptions.

For too long librarians and library science educators saw ourselves as neutral actors. We collected, described, and provided materials believing that these acts were either without bias, or that those biases were controlled. In collecting we took it all…except for works that were self-published, or from sources we deemed predatory or of low quality. In cataloging we relied on literary warrant and the language of the community – often ignoring that we only saw the dominant narrative and voices. Our services were for all – from 9 to 5 with a researcher’s card who could travel.

We as a profession are now waking up to the fact that we are a product of our cultures – good and bad. We understand that the choices we make in everything from classification to exhibits are just that – choices. They may be guided by best practice, or enforced by law, but ultimately, they are human choices in a material world where resource decisions must be made. We can speed up digitization with newer machines, but we still have to pick a starting point. We can expand those we serve on the web, but still must acknowledge that there are people with no broadband or connectivity.

Now it would seem like this may turn to a call to redouble our efforts in neutrality. A call to wipe away the biases in ourselves so that we can confront the cost to society of skewed machine learning efforts. But it is not. In fact, we must embrace that libraries, and the librarians that build and manage them, are biased[12]. What’s more, it is only by seeing libraries as biased that we prove our value in the world of massive scale data.

First, we must realize that it is impossible to be neutral. Putting a book on a shelf or in a vault is a choice. Every day in archives and special collections we make professional determinations of how accessible an item is versus how protected it is. We can seek out many voices and yes, gather data, to make those decisions, but in the end, they are decisions with consequences. Pretending we are neutral doesn’t change the consequences, it only allows us to pretend they are not the result of our action.

Now, I keep calling them biases, but a better word would be principles. Principles are an explicit statement of belief. They should be transparent and, most importantly, able to be assessed. Are we following our principles?

And make no mistake principles are not neutral. Seeking to serve all equitably takes effort and resources. Choosing to provide images for fee or free is a choice. Fighting censorship is a decision. If you don’t think so, try balancing it against issues of hate speech and threats to marginalized communities.

It is in our decisions and our transparency in making those decisions that we build trust with our communities. Our scholars, and entrepreneurs, and citizens don’t trust librarians because we are neutral, but because they agree with our principles and see them consistently applied. The days when libraries had the monopoly on access to large collections is well over. Yet libraries in most places the world are not only in use, but in growing use – public, academic, school, and national libraries alike.

Where library use (not necessarily support, but use) is growing it is because we are seen as accessible, equitable, and trusted. Yes, the collections we hold are valuable. The fact that we hold unique resources that either haven’t been, or can’t be digitized is important. But it is only important if those who seek out these resources trust us to be honest stewards of these resources.

It is our embrace of our humanity – our human touch in an increasingly automated system that underlies our value. This is not a luddite’s call against technology, AI, or machine learning. Rather it is a belief that human connection – community- is more important than ever when the face of government and business alike become web pages and bots under the banner of austerity or efficiency.

The future of libraries is ultimately not set by which technologies are developed or deployed. It is not in a value that was defined a century ago. It is in our very human ability to build trust with our communities. It is upon that trust that we build support. It is upon that trust that we build use. It is upon that trust that we find and confirm our necessity.

It is with that trust that we must reach out to the computer science community, the online industry, and the governments collecting data and deploying algorithms. We must advocate for a seat at the table and represent the voices of those without a seat. We must use the hard lessons we learned and are still learning in issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion to help guide these technologies. We must be trusted by our communities to speak truth to power and to give those communities power to speak for themselves. We must follow our principles in actively shaping, with our communities, the policies, regulations, and laws that talk about data.

National libraries must play a large role in civic data stewardship. National libraries must not just safe guard the heritage of cultures, but the privacy and intellectual safety of citizens. You need to be a memory organization in the realization that effective memory is both about remembering, and, forgetting.

How do I resolve the paradox that I just advocated for a common role in institutions that I also acknowledge are so diverse? If indeed, you each represent unique institutions, does this preclude collective action? Of course not. Because in effect you are what all libraries must become. Every library- public, academic, school- should be shaped to the communities they serve. Then, as librarians, we become the connective tissue that seeks the best of all libraries and shape those innovations to local needs. Gone are the days when every library looked alike or supported some cannon of common services. Gone are the days when best practices extend to all libraries of a given size or type. Throw away the toolkits and instead build a toolbox[13].

We must prepare our librarians, regardless of title, or training, or location to be a missionary force proactively engaging in the well-being of our cultures and communities. We must build national peer networks that rapidly and effectively spread ideas and help librarians effectively shape them when they meet local needs. These networks discard best practice and industrial standardization for conversation, learning, and adaptation. We must connect the best thinkers together regardless of status or institutional boundaries.

How do important national institutions do this?

We must create platforms for continuous engagement of librarians where they can share, learn, teach, mentor and support each other. This may be built upon and with national and regional associations, but the focus is on individuals, not institutions.

We must create a system to formally recognize participants within and beyond this platform. Work with library science programs where they exist, but also extend the recognition beyond formal degrees to continuous learning.

We must recognize Lighthouse Libraries[14]that embody innovation and serve as inspirations, not blueprints, for other libraries.

We must proactively engage this network of change agents to transform libraries, associations, institutions, and ultimately communities globally. Members of our peer networks, our communities of practice, must encounter daily new ideas from across the globe.

Think of a library as movement, not a place or an institution[15]. It is a movement of people committed to improving society. Librarians, certainly. But also, scholars, politicians, entrepreneurs, programmers, and authors. Discard terms like users that reinforce the idea that our communities are consumers, and our only value is in the utility we provide to a demand. We have members and citizens; neighbors and scholars that all own and shape the library.

Most importantly, this will not happen in one hour of a conference. It will take more engagement, more experimentation, and more investment. That is why I support the PL2030[16]project. Building off of the Public Libraries 2020 project, it is a group of librarians from across the continent seeking to transform public libraries across Europe one librarian at a time. It advocates for libraries and builds connections between elected representatives and library innovators. But it needs help.

PL2030 and the work of its members represent the need for a new vital link between the cultural heritage mission of National Libraries and public libraries. Libraries are transforming from access points, collections, and information providers into community hubs across Europe. From Manchester to Cologne to the amazing Dokk1 in Aarhus to Delft and Tilburg in the Netherlands and Pistoia and Perugia in Italy public libraries are the places communities come to learn, create and dream together. Here, by the work of innovative librarians, libraries have gone from quiet places of retreat to loud places of engagement. The true collection of a great public library is now the community itself. Blacksmiths and bakers host conversations. Librarians lend out books and musical instruments and recording studios. Rather than bringing the world to the community, these libraries have become loudspeakers broadcasting the community to the world. These public libraries have become the cradle of cultural creation.

As institutions charged in part with preserving and supporting the cultural heritage of a people, you need to preserve and support the work of these institutions. Not simply as a backup or for posterity, but as part of the living and breathing centers of community conversation. In a connected world – connected through technology certainly, but also in trade, in governance, and in preserving the earth itself – There is no more front-line service and library of last resort. We librarians are obligated to serve all, and in your nations now is a network of libraries eager for your partnership.

I thank you for your time, and I look forward to the conversation to come.

[1]Or “Memory Institutions” like the CENL Strategic plan https://www.cenl.org/wp-content/uploads/CENL-Strategy-2018-2022_final-1.pdf

[2]https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/George_Santayana

[3]I love Chris Bourg’s take on the use of “societal cost” in discussing AI versus ethics.

[4]I’m a big fan of the British Library’s https://www.bl.uk/business-and-ip-centre

[5]http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/881631924

[6]https://theintercept.com/2018/11/13/google-quayside-toronto-smart-city/

[7]https://www.torproject.org/

[8]There are plenty of good articles explaining VPN. Here’s one that actually compares VPNs vs Tor: https://www.cloudwards.net/vpn-vs-proxy-vs-tor/

[9]http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1039545320

[10]http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1060991037

[11]This article certainly doesn’t claim that all of cultural heritage can be represented quantitatively. Rather I include the citation because it is a good introduction to the use of quantitative analysis of some cultural material and because it includes the very cool term Culturomics, “Culturomics is the application of high-throughput data collection and analysis to the study of human culture.” https://www.librarian.net/wp-content/uploads/science-googlelabs.pdf

[12]Here’s a good place to start on the discussion of libraries, librarians and neutrality:https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2018/06/01/are-libraries-neutral/In particular check out Emily Drabinski’s take.

[13]Pithy phrase, but in case it is not clear I mean stop sending out assembled ready to implement toolkits and focus on librarians gaining the tools to develop their own programs and/or create local application of programs customized to their communities.

[14]https://publiclibraries2030.eu/projects/lighthouse-libraries/

[15]Stole this idea from the amazing Marie Østergaard: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/princh-library-lounge-ep-3-building-global-networks/id1451326347?i=1000437039135

[16]https://publiclibraries2030.eu/