In a previous post I talked about a potential path of disaster for public libraries. The TL;DR version is that if public librarians and their libraries seek to be all things to all people they will ultimately be stretched too thin and become the poster children for ineffective government. This is particularly true in light of shrinking services by government agencies. Within that argument (or rather the solution provided) are the seeds of a massive disruption in public services in general. In this post I’m going to expand on those seeds. I am going to start this discussion of public services in the obvious place: collections.

The past 6 decades have seen an unprecedented change in how librarians view collections. Libraries, by and large, have been fixated on documents (or more broadly “document like objects”). The documents were physical, fixed, and owned. If a library wanted to add something to a collection they bought it, they described it, and they placed it.

Libraries then began to expand from documents to other media (to be precise there have always been libraries that collected varying media – I’m talking about the majority) like films, audio recordings, and eventually tapes, CDs and such. Still, the model was of objects owned, described, and placed.

A massive shift in how we conceptualized library collections occurred with the advent of databases. While at first CD’s were little more than digital version of paper reference resources databases quickly represented a massive change in collection content and library business models. In terms of content with the advent of journal databases libraries made available huge quantities of materials that librarians had only a cursory knowledge of. Librarians were now advanced searchers, often discovering what they library “held” right alongside our members.

Electronic databases, CDs, then online databases, also represented a massive departure in the business model of libraries. Where once the majority of resources in the collection were owned, now the vast majority of items (counting articles as items) were rented through fixed term licenses. We are only now feeling the full repercussions of this shift as these licenses have become increasingly expensive; swallowing the collection budgets and more of many institutions.

The Internet was (is) the next major expansion of the concept of collection in libraries. Now anything anyone could put on a page or attach to a URL was part of the collection. That actually wasn’t the biggest conceptual shift though (after all by this point librarians were into discovering resources without previous knowledge of them). No, the biggest shift was that the Internet was not populated with just document like objects, but with services, software, and capabilities. Our collections went from documents, to documents and media, to documents and Facebook, and Google, and Twitter, and real-time video.

While librarians have not fully adjusted to these changes, nor integrated them together (and major issues of preservation still remain a huge challenge), for the most part libraries have successfully transformed to encompass the idea of a library collection as dynamic, open, and important. With each change came stress and discord. Each step turned into a flurry of experimentation and eventual standardization. But on the whole, what once looked like a change that would end libraries is now seen as beneficial. Librarians have not only changed how they see the collection but we have brought our communities along with us. People expect to access databases, and the Internet as well as physical collections. No one really questions any more the use of Google at the reference desk. No one bats an eye when public access computing incorporates gaming alongside Lexus/Nexus.

So we all deserve a big pat on the back. It has been an astounding half-century plus of change, but we did it. We are a different profession because of it, and we are relevant. Yea! No one should underestimate the scale of this disruptive change. But I have bad news…it is time to do it again – massive disruptive change that is.

As our collections have changed, we have added services to our communities (schools, universities, towns, firm, etc.). Where once we provided faster more efficient access to physical items, we added question answering, eventually question answering both at a desk, embedded in teams, and online. We added instruction; first about the library (bibliographic instruction), but eventually around information literacy. We added readers’ advisory, story time, and more recently maker spaces, fishing pole lending, and so on. Once could say that our public services have seen massive change – but I disagree.

As our collections changed, being in a profession primarily concerned with collections, we’ve expanded and shifted our services. However, we have not fundamentally changed them. You see for all of these new services we still cling to a very simplistic service model…us and them: librarians and patron; library and community. We still see the role of the library to serve a community, and in that, to be slightly apart from it. That is problematic because it leads right back into an assured path to irrelevance or an outright impeachment of our basic principles.

Irrelevance? This was my argument in my previous post on the death of public libraries. If librarians continue to see their role as serving a community, and attempting to meet their shifting needs, librarians will be stretched too thin. Librarians will have to become expert searchers, researchers, makers, tax experts, employment advisors, social workers, tutors, and so on. This has lead to many libraries co-locating services such as in a commons model that brings access to librarians, technologists, and learning specialists. We have seen libraries hire social workers, anthropologists and so on. However, if librarianship doesn’t expand to incorporate these services at a fundamental level, we end up with stovepipes of services that sit in an organization or physical space, but gain little from the colocation. In essence, we treat tutors, and anthropologists, and such as just another expansion of the collection.

The other problem is the collocation of services without a radically different service model leads to a diffuse definition of what a library is. We can lose the support of our communities as they struggle to figure out our unique value. Worse still, by adopting new services and offerings based solely on the demands of a community, we can easily fall into a “customer perspective” where we scramble to meet the desires of a community regardless of how they align with core values such as openness, privacy, intellectual freedom, and such. Libraries go from safe, principled spaces of learning to simple gateways to subsidized services…easily disrupted, and easily replaced or discarded.

Librarians want to answer questions or solve problems put to them. In the days of virtual reference we coined the phrase “the greedy librarian problem.” It was observed in service after service, institution after institution, that librarians would receive a reference question, and do their best to answer that query – even if they could pass the question off to someone else (another librarian or an expert) who was better qualified to answer it, or could answer it faster. This came from both a STRONG service ethic, and professional preparation that taught the idea of a generalist librarian.

We are again facing the greedy librarian problem, but now it is in the form of a librarian as social worker, a librarian as maker, a librarian as business expert. If it is offered under the egis of the library, than a librarian must master the content first, then offer the program. This is bad. Bad not in that librarians can become experts in things other than librarianship, but bad in that they may feel that librarianship is expertise in all other areas.

The disruptive change we need now is in removing boundaries between library and community. I have often said, “the community is the collection.” That is more than a rhetorical slogan meant to focus people on “user services.” I mean it literally. If all libraries do is talk to their communities to add new services, or adopt social media to broadcast library events, or become more responsive at a desk, they have not engaged in the necessary and fundamental change needed.

What we need is a merger of collection and community. This is the disruptive, fundamental, and radical shift. In the community you serve, people consume, sure. However, they ALL create, even if they are only creating knowledge within themselves. The power of a new necessary model for public service is to see people in your community as creators who are willing to share their expertise, their understandings, and their resources (like tax dollars, or tuition dollars, or budget lines AND their books). People within your community are willing to teach, and develop programs, and tutor, and the like.

The key massive shift in public services need to make this change? For those familiar with my work, you may find my solution a bit out of character: collection development. Yup. The same skill that has gone through such dramatic changes from documents to media to databases to the Internet, to services. Except, it is development of the community and its conversations.

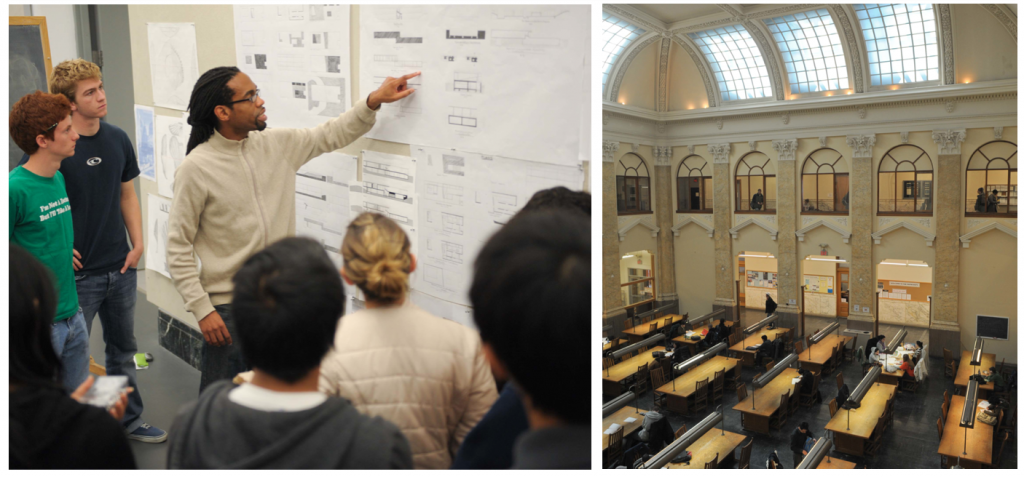

An example may be in order. A man comes into the library and through conversing with the librarian offers to teach sessions on self-publishing. Now, the first thing that must change is how the librarian responds to the idea of a self-publishing program. Gone is the idea that the librarian will go learn everything there is to know about self-publishing and then start offering programs around the topic. The community member says they already have that knowledge, so they should teach it. Ah, but you say, how do I know they are any good. Do they know about self-publishing? Have they done it? Can they teach? Will they present in a way that upholds the principles of librarianship (intellectual honesty, transparency, and so on)? This is the role of the librarian. This is collection development.

Maybe they can’t teach – great, either the librarian can get them some experience in it (like linking them up with another community member who can act as a mentor) or suggest they put together a libguide, or a curated collection of resources to share. Maybe they only have experience with one platform, can the librarian hook them up with someone with other experiences, or set up complementary programming. Collection development.

In this approach the wall of service between library and community disappears. The librarian is directly working with the community to expose expertise and offer service through the community not to the community. Librarians don’t have to know all the community knows, but they must be able to weave it together and link it. The library becomes a platform not for resource sharing, but for community building and connections.

This then is the next hurdle and challenge: making the community our collection. We have many of the pieces in place. We have an expanded view of collection and the distributed tools that come with it. We have a new definition of librarianship not linked to any particular institution, but focused on knowledge and community. We have some examples of this happening from general approaches like patron driven acquisitions to specific institutions like Chattanooga, Ferguson, and Fayetteville Free. We have the love of our communities. We have spaces to gather. We have an army of professionals and aligned staff in nearly every community in North America.

Now is the time. We can change the world not by informing a community, or serving it, but by unleashing it. We will advance our communities, our nations, and society not by waiting to serve, not by pushing from behind, nor invisibly advocating issues of social justice. We will move forward society by standing side by side with the teacher and the student, the cop and the community, the philosopher and the blacksmith. Librarians, and the institutions they build with their communities, libraries, will, with radical zeal, interweave human capability for greatness. Let’s get to it.