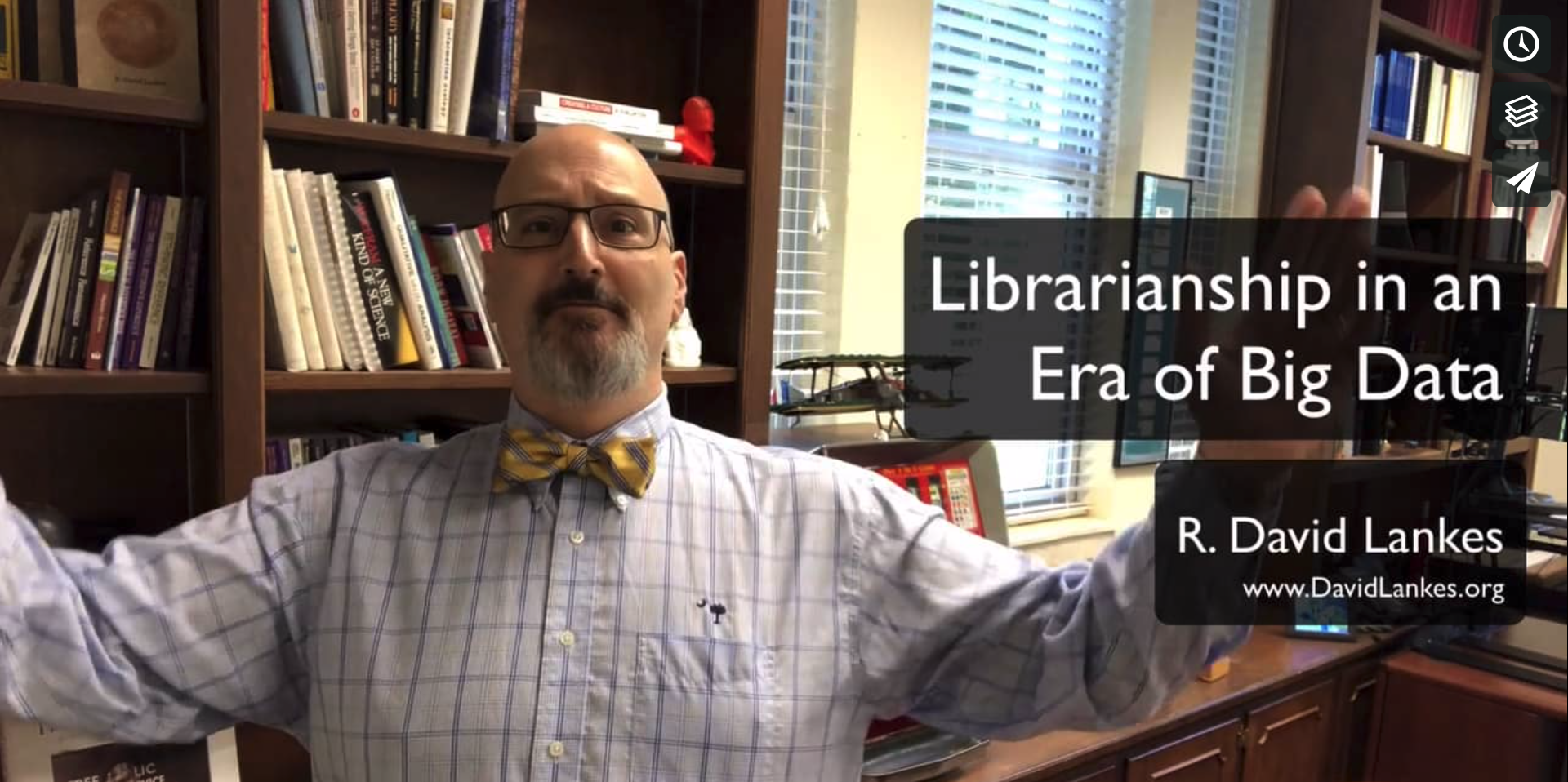

“Decoding AI and Libraries.” KB College: AI en de Bibliotheek – de computer leest alles. The Hague, Netherlands. (via video conference)

Speech Text: Read Speaker Script

Abstract: How can we think about AI and the role of libraries in AI development?

In the 90s I was working on a project called AskERIC – a service that would answer questions of educators and policy makers online. It was early days of the web, well before Google, Facebook, or Amazon. Yet even then we would regularly get questions about artificial intelligence; “i.e., Can’t machines answer these questions?” My boss’ answer was great – “We’ll use natural intelligence until artificial intelligence catches up.”

A quarter century later, artificial intelligence has done some significant catching up. From search engines to conversational digital assistance to machine learning embedded in photo apps to identify faces and places, the progress of A.I. is breathtaking.

The last 10 years of progress is particularly impressive when you realize that A.I. has been a quest of computer scientists since before there was such a thing as computer science.

Today the larger conversations of A.I. tend to be either utopian

A.I. will improve medicine, reduce accidents, and decrease global energy use

or dystopian

It will destroy jobs, privacy, and freedom.

A.I. has also become a bit of a marketing term – soon, I fear we’ll be eating our cereals fortified with AI.

The hype and real progress have merged into a bit of a jumbled mess that overall can lead to a sort of awe and inaction.

Awe in that many of us in the library, and particularly public library community, may feel the details are over our head. A.I. is a game for Google. Inaction because the topic seems too big – what role is there for a library when these tools are being created by trillion-dollar industries?

True story, the same day my dean asked me about the possibility of creating a degree in data science and A.I., MIT announced a Billion Dollar plan to create an A.I. college[1]. I don’t think he appreciated me asking him if I would have a billion to work with as well.

I’ve found these reactions – awe and inaction – are often a result of muddled vocabulary. So, for my contribution to today’s agenda, I’d like to briefly break the conversation down into more precise, and actionable concepts. My focus here will be in the contribution of public libraries, but I believe that the concepts are not only relevant to other public sector organizations but can only be truly implemented with partners of all types.

So rather than just think of A.I. as a big amorphous capability, I ask you to think about three interlocking layers: data, algorithms, and machine learning.

Ready access to masses of data has led to high-impact algorithms and increasingly to machine learning and black box “deep learning” systems. If we, librarians do not seek to have positive impacts at each of these levels – well, to be blunt – I would argue we are not doing our job and putting our communities in danger.

So, let’s begin with data.

The first thing that gets thrown into the A.I. bucket is the idea of data or big data. From data science to analytics there is a global uptick in generating and collecting data. With the advent of always connected digital network devices – read smart phones – in the pockets of global citizens, data has become a new type of raw resource.

And when I say global, I mean it. In 2010 the United Nations reported that there are far more people in the world that have access to a cell phone than to a toilet.

With this connectivity, most in society have simply accepted that one of the costs to being connected is sharing data. Sharing it with a carrier and sharing it with the company who wrote the phone’s software. Apple or Google probably know right now where you are, who you’re with, and if you use Siri or Google Assistant, they are primed to be listening to what you might be saying right now. No, I mean literally, right now.

The phone thing probably doesn’t surprise you. But what about the road you used to get here today? When governments build or repave a road, there is a good likelihood they are embedding sensors into it. Why? Well one reason is to save the environment and money in northern climates. How? In the winter rather than just lay down salt or chemicals on every mile of road, smart sensors can pinpoint where ice melt is needed, and reduce the application of costly chemicals.

Sensors are also used to determine the amount of traffic on the road, when to change signal lights, collect tolls, and check for wear and tear.

Add to this the data generated by cars on the road – digital radio, GPS, increasing autonomous driving – and the data begins to add up.

In fact, by one estimate in a few years each mile of highway in the U.S. will generate a gigabyte of data an hour. As there are 3.5 million miles of highways in the U.S., that would be 3.3 petabytes of data per hour, or 28 exabytes per year.

Just in case you are wondering, five exabytes is enough to hold all words ever spoken by humans from pre-history to about the year 1995. Now imagine over 5 times that a year, just on asphalt.

Now that may seem overwhelming, but at the data layer there is a lot of need, and space for libraries to participate. The questions to ask and develop answers to are familiar. Who has access to that data? How is that data stored and how do you find anything in that exabyte haystack? How do we make people aware of the data they may be sharing? How do we advocate for effective regulation to protect citizens?

I argue that public libraries should be steward of public data. Libraries have a VERY long history of data stewardship that includes respect for privacy and seeking equitable access to information. If we are going to allow our governments and our businesses to harvest data then we need to ensure our communities have a strong say in how that happens and trust in those that make the decisions. Right now, libraries have a stronger level of trust than Apple, Google, Facebook, and most elected governments[2].

The accumulation of data in and of itself is not particularly alarming. As libraries have shown over and over again having a bunch of stuff means nothing if you don’t have systems to find it and use it. This takes us to our second layer of concern in A.I.: algorithms.

Companies and governments alike are using massive computing power to sort through data, much of it identifiable to a single individual, and then these folks make some pretty astounding decisions. Decisions like which ad to show you, or what credit limit to set on your credit card, to what news you see, and even to what health care you receive. In our most liberal democracies software is used to influence elections, and who gets interviewed for jobs.

Charles Duhigg, author of “The Power of Habit[3],” tells the story of an angry father who storms into a department store to confront the store manager. It seems that the store had been sending his 16-year-old daughter a huge number of coupons for pregnancy related items: diapers, baby lotion and such. The father asks the manager if the store is trying to encourage the girl to get pregnant? The manager apologizes to the man and assures him the store will stop immediately. A few days later the manager calls the father, only to find that the daughter was indeed pregnant, and the store knew it before she told her father.

What’s remarkable is that the store knew about the pregnancy without the girl ever telling a soul. The store had determined her condition from looking at what products she was buying, activity on a store credit card, and in crunching through huge amounts of data. If we updated this story from a few years ago we could add her search history and online shopping habits, even her shopping at other physical stores. It is now common practice to use online tracking, WIFI connection history, and unique data identifiers to merge data across a person’s entire life and feed them into software algorithms that dictate the information and opportunities they are presented with.

In her book “Weapons of math destruction[4],” Cathy O’Neil documents story after story of data mining and algorithms that have massive effects in people’s lives, even when they show clear biases and faults. She describes investment algorithms that not only missed the coming financial crisis or 2008, but actually contributed to it. Models that increased student debt, prison time for minorities, and blackballed those with mental health challenges from jobs.

The recurring theme in her work is that these systems are normally put in place with the best of intentions.

And here we see the key issue in the use of software to crunch massive data to make decisions on commerce, health care, credit, even jail sentences. That issue lies in the assumptions that those who use the software make. Often very dubious, and downright dangerous assumptions. Assumptions such as algorithms are objective, and that data collection is somehow a neutral act. Or even, that everything can be represented in a quantitative way – including, by the way, culture[5]and the benefit a person makes to society[6].

What role is there for librarians, curators, and academics here? The answer on the surface is about the same as in our discussion of data. Education, awareness, a voice in regulation. However, we must be very aware of the nature of our voice.

For too long librarians saw ourselves as neutral actors. We collected, described, and provided materials believing that these acts were either without bias, or that those biases were controlled.

In collecting we took it all…except for works that were self-published, or from sources we deemed of low quality. In cataloging we relied on literary warrant and the language of the community – often ignoring that we only saw the dominant voices of that community. Our services were for all – during our open hours for those who could travel to our buildings.

We as a profession are now waking up to the fact that we are a product of our cultures – good and bad. We understand that the choices we make in everything from collections to programs are just that – choices. Our choices may be guided by best practice, or even enforced by law, but ultimately, they are human choices in a material world where resource decisions must be made.

So as a library we are not asking to be neutral arbiters of data collection and uses. We are seeking to improve society through data and algorithms – that means we have a point of view. We have a definition of what improve means.

However, the biases we bring, or more precisely the principles, we bring to the Googles and Facebooks of the world is that a strong voice that advocates for transparency, privacy, the common good, and a need for a durable memory is important.

We recognize that bias exists even if we can’t always identify it, and so we require diversity and inclusive voices in our work. In this act we are not simply advocates, we are activists. A missionary corps of professionals equipping our communities to fight for their interests.

And this brings us to our last layer. The layer that most purists would say is true artificial intelligence development. The use of software techniques to enable machine learning, and especially the more specific deep learning.

That is, software that allows the creation of algorithms and procedures without human intervention. With techniques like neural nets, Bayesian predictors, Markov models, and deep adversarial networks software sorts through piles and piles of data seeking patterns and predictive power.

An example of machine learning systems in action would be feeding a system a number of prepared examples, say hundreds of MRI scans that are coded for signs of breast cancer. The software builds models over and over again until they can reproduce the results without the prepared examples. The trained system is then set upon vast piles of data using their new internally developed models.

With the wide availability of massive data, newer deep learning techniques do away with the coding, and go straight to iterative learning. Where machine learning used hundreds of coded examples, deep learning sets software free on millions and millions of examples with no coded examples – potentially improving the results and eliminating the labor-intensive teaching phase.

When this works well, it can be more accurate than humans doing the same tasks. Billions of operations per second finding pixel by pixel details humans could never see. And they can do it millions and billions of times never tiring, never getting distracted.

In these A.I. systems there are two issues that librarians need to respond to. The first is that these machine-generated algorithms are only as good as the data they are fed. MRIs are one thing, credit risks are quite another. Just as with our human generated algorithms, these systems are very sensitive to the data they work with.

For example, a maker of bathroom fixtures sold an AI-enhanced soap dispenser. The new dispenser reduced waste because it was extremely accurate at knowing if humans hands were put under the dispenser or say a suitcase at an airport. Extremely accurate, so long as the hands belonged to a white person. The system could not recognize darker skin tones[7]. Why? Was the machine racist? Well, not on its own. It turns out it had been trained on only images of Caucasian hands.

We see example after example of machine learning systems that exhibit the worst of our unconscious biases. Chat bots that can be hijacked by racists through Twitter, job screening software that kicks out non-western names. Image classifiers labeling images of black people as gorillas[8].

However, bad data ruining a system is nothing new. If you’ve had about 10 seconds of work migrating integrated library systems, you know that all too well.

The real issue here is that the models developed through deep learning are impenetrable. That MRI example looking for breast cancer? The programmers can tell you if the system detected cancer, even the confidence the software has in its prediction. The programmer can’t tell you how it arrived at that decision. That’s a problem. All of those weapons of math destruction Cathy O’Neil described, can be audited. We can pick apart the results and look for biases and error. In deep learning, everything works until, well, an airplane crashes to the ground or an autonomous car goes off the road.

And so what are we to do? This is tricky. There can be no doubt that data analytics, algorithms taking advantage of massive data, and A.I. have provided librarians and society great advantages. Look no further than how Google has become one of a librarian’s greatest tools because it provides not only the ability to search through trillions of web pages in milliseconds, but often serves as a digital document delivery service undreamed of 25 years ago when I was working on AskERIC.

And yet, we still need that natural intelligence my boss, Mike Eisenberg, talked about.

Our communities, and our society, needs a voice to ensure the data being used is representative of all of a community, not just the dominant voice, or the most monetizable. Our communities need support, understanding, and organizing to ensure that the true societal costs of A.I. are evaluated, not simply the benefits.

That may sound like our job is the be the critic or even the luddite, holding back progress. But that’s not what we need. Librarians need to become well versed in these technologies, and participate in their development, not simply dismiss them or hamper them. We must not only demonstrate flaws where they exist but be ready to offer up solutions. Solutions grounded in our values and in the communities we serve.

We need to know the difference between facial identification systems, and facial identification systems that are used to track refugees. We need to know the difference between systems that filter through terabytes of data, and systems that create filter bubbles that reinforce prejudice and extremism.

And today is a great first step to honoring that responsibility.

Thank you, and I look forward to the conversations to come.

[1]https://www.technologyreview.com/f/612293/mit-has-just-announced-a-1-billion-plan-to-create-a-new-college-for-ai/

[2]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tvt-lHZBUwU

[3]http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/881631924

[4]http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1039545320

[5]his article certainly doesn’t claim that all of cultural heritage can be represented quantitatively. Rather I include the citation because it is a good introduction to the use of quantitative analysis of some cultural material and because it includes the very cool term Culturomics, “Culturomics is the application of high-throughput data collection and analysis to the study of human culture.” https://www.librarian.net/wp-content/uploads/science-googlelabs.pdf

[6]https://www.businessinsider.com/china-social-credit-system-punishments-and-rewards-explained-2018-4

[7]https://www.iflscience.com/technology/this-racist-soap-dispenser-reveals-why-diversity-in-tech-is-muchneeded/

[8]https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/jul/01/google-sorry-racist-auto-tag-photo-app