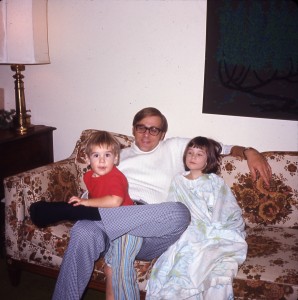

16 years ago today my father died. I think of him often, and miss his wit and guidance. It is also not lost on me that he was just about 10 years older than me now when he died. As I grow older, I remember him and our time together differently. There is a nuance where I am either understanding our time together differently, or I am simply projecting my own time as a father into his actions.

16 years ago today my father died. I think of him often, and miss his wit and guidance. It is also not lost on me that he was just about 10 years older than me now when he died. As I grow older, I remember him and our time together differently. There is a nuance where I am either understanding our time together differently, or I am simply projecting my own time as a father into his actions.

As a bit of a remembrance of dad, I’m posting another excerpt from my new book The Boring Patient. It is the first time that I have really written about my dad and his passing. I also think that my father, as the consummate salesmen, would appreciate me using his memory to drum up sales.

The Family

Once my medical team suspected cancer my wife called my mother to tell her the news. My mother, who lives in Ohio, was in a car in Tennessee on her way to Florida when she got the call. She found the closest airport and flew to Syracuse the next day to be with me and help out at home.

It took me a few days to truly understand the depth of my mother’s concern. Somehow in my 40s I had forgotten that I was still her son. If my son was diagnosed with cancer you better believe I would be in that hospital room. My mom was there for the first chemo, and she was there when we had to tell my two sons what was going on. In a way my father was there too, even though he had died over 15 years ago at just 55 years old.

I was at my father’s bedside when he died. He had gone to the hospital complaining of abdominal pain. He had a gallstone (thanks genetics). Normally, as I have said, this is painful, but not dangerous. Your liver makes bile, a soup to help you digest fats, and stores it in the gallbladder, which spits it into your small intestines via the bile duct when you eat. A gallstone is when some of this soup hardens sitting around in the gallbladder. If that “stone” finds its way to the bile duct and gets stuck? Ouch!

In a small part of the population the bile duct joins up with something called the pancreatic duct before it joins the intestines. The pancreatic duct delivers digestive juices (technical term) into the small intestines. The problem is if a gallstone stops up a joint duct like this, particularly just after you have eaten: not only do you get the pain of a backed-up gallbladder, the pancreatic juices also back up into the pancreas, causing acute pancreatitis. There is no elegant way to put this: the pancreas begins to digest itself. If this can’t be controlled, these juices begin leaking out of the pancreas and this leads to organ failure. My father was part of that unlucky population.

In a small part of the population the bile duct joins up with something called the pancreatic duct before it joins the intestines. The pancreatic duct delivers digestive juices (technical term) into the small intestines. The problem is if a gallstone stops up a joint duct like this, particularly just after you have eaten: not only do you get the pain of a backed-up gallbladder, the pancreatic juices also back up into the pancreas, causing acute pancreatitis. There is no elegant way to put this: the pancreas begins to digest itself. If this can’t be controlled, these juices begin leaking out of the pancreas and this leads to organ failure. My father was part of that unlucky population.

I was 28 when this happened. I still think about my father every day. By the time I got home to be with him the doctors had put my father into an induced coma for the pain. He never woke up. He died surrounded by my mother and me and some friends. As we told stories and laughed celebrating his life his vital functions slowed. At the moment his heart stopped a doctor and nurse rushed into the room to revive him. However, he wanted no “heroic measures,” and his doctors had made it very clear that they had done everything that could be done and there was no chance for recovery. So my mother, with a strength I cannot fathom, stayed the hands of the doctor.

I would note, however, that his heart, an organ that he had struggled with (a quadruple bypass, multiple stents, and endless battles over smoking and a bad diet) was the last thing to go. “Listen son, I could get hit by a bus tomorrow,” he would say as he downed a fried baloney sandwich. After his bypass he had me bring Kentucky Fried Chicken to his hospital room. I believe it was my father’s final “screw you” to the doctors that the heart went last. He was a man with a great sense of humor so I wouldn’t put it past him.

I would note, however, that his heart, an organ that he had struggled with (a quadruple bypass, multiple stents, and endless battles over smoking and a bad diet) was the last thing to go. “Listen son, I could get hit by a bus tomorrow,” he would say as he downed a fried baloney sandwich. After his bypass he had me bring Kentucky Fried Chicken to his hospital room. I believe it was my father’s final “screw you” to the doctors that the heart went last. He was a man with a great sense of humor so I wouldn’t put it past him.

My father’s death made me (and still makes me) think a lot about my kids and being left fatherless. I have two sons that my dad never got to meet. Riley was 12 when I was diagnosed. Andrew was 9.

There was not much debate between my wife and me when it came to informing the kids. Be open and honest and ready to answer all their questions. I don’t think the idea of hiding my condition from my kids ever really occurred to us. Yet, I have had several folks tell me about having a parent die of cancer, and never being told what was going on. They told me they are still dealing with that as an adult. We didn’t want that.

For Andrew the talk was relatively easy. Daddy is sick. He has cancer. He will be tired and probably lose his hair. Andrew didn’t really have a grasp on death and such, so to him, it was just some more information. “Can I get ice cream now?”

Riley’s talk was tougher. There are way too many ways in which my eldest son is like me. One way that was evident during this conversation was using humor to mask our emotions and/or break the stress. With every bit of information he made a joke while clearly tearing up. Finally, at the end he said, “Yeah, but it’s not like you’re going to die.”

“Actually son, yes, I could die.” May you never have to say those words to your child.

The only thing that saved me from breaking down at that point was having my wife and mom in the room. “But grandma had cancer, and she’s fine. Uncle Joe had cancer, and he’s fine.” Never mind that he remembered Joanne who had died from cancer, and his good friend’s mother. Riley is smart. Riley knew the possibilities. Later, however, Riley would also be the first to make jokes about my lack of eyebrows and hair. All of Riley is smart, including his ass.

You can read more about my family and our trip through cancer in The Boring Patient, now on sale.