[This is an edited version of the script I used for my talk. However, it is not a word for word transcript. Aside from added comments during the talk, I have edited and expanded the notes here to make them more readable. You can see a screencast of the actual presentation here.]

When I was invited to give this talk, Kim Tallerås told me that I could address:

- What technological expertise should librarians have?

- What should we leave to other professions?

- Generalist vs specialist?

- What does knowledge organization mean in 2017?

A simple list, right? I particularly like the “etc” just in case I might have some extra time.

So where to begin? I could start with my opinion. I could start with the curriculum that we are developing at the University of South Carolina. I could, of course, pretend to answer the questions by “framing the debate,” where I list some international competencies, throw in a bit of criticism, but really leave the questions unresolved.

Instead, let me start with a question that isn’t on this list: are there right and wrong answers to these to begin with? Is there some foundation that we can test our opinions? Because it turns out what looks like topics for debate, are in fact answerable, but only if we start from a firm foundation.

Here I need to ask for your patience, because I need to start with some abstract concepts, but I promise the payoff of concrete answers.

So I start my answers with yet another question: what is a librarian?

After all, how can we answer whether a librarian should be a technologist, or specialist unless we have a concrete starting point. The definition that many in the profession – and most outside of the profession – use, “a person who works in a library,” is woefully inadequate.

It fails for two major reasons:

- There are plenty of librarians that do not work in a library. They may be consultants, or work for corporations such as Elsevier, Dynix, or Google, as analysts, researchers, etc.

- There are plenty of people who work in libraries that are not librarians – janitors, volunteers, human resource professionals.

There is a third reason, we don’t have a good definition of a library to begin with, but I won’t go into it here.

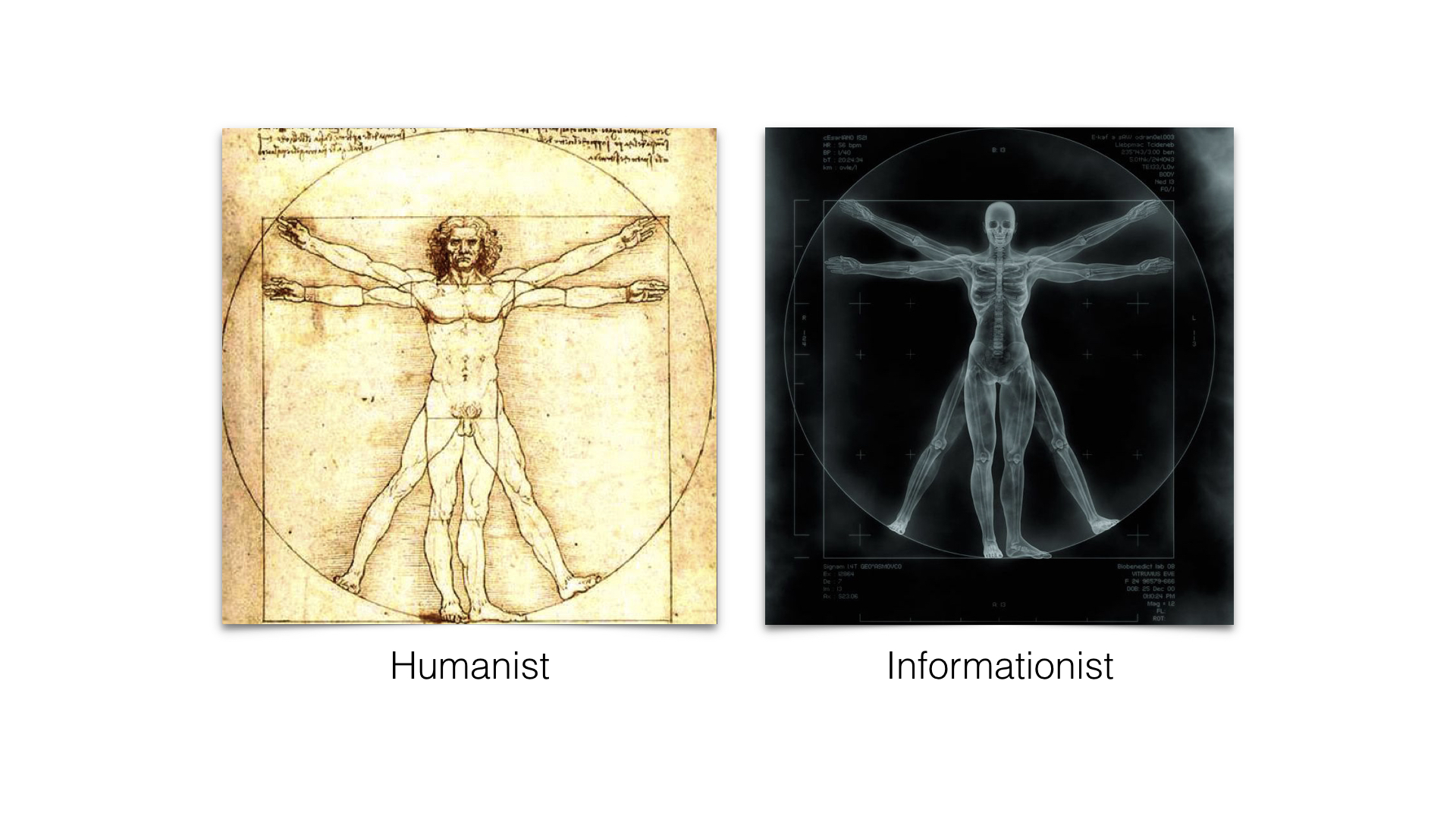

So if not by the institution in which librarians work, how can we define them. There are certainly traditions we can look to. A long standing one, and a tradition that is regaining strength, I will call the humanist tradition. Though perhaps I should call it a humanities tradition as all too often it focuses on materials and “texts” over people.

This tradition is strongly influenced by documentalism, cultural heritage, and the humanities. In this tradition a librarian is a curator of a collection. A librarian is a sort of curator of the cultural transcript. They seek standards for selecting and organizing materials for their patrons.

Another tradition we could look to is more modern and one that certainly predominates the field in many parts of the globe. I will call it the information tradition. Here a librarian is a sort of super information processor; adept at navigating data and often disembodied information to meet a user need.

To be clear, both of these traditions are presented here more as caricatures for argument to focus on their shortcomings.

The problem with these two traditions is that they are just that – traditions and grounded more in perspectives and nostalgia then an actionable framework. They are also messy. The humanist knows the cultural transcript is increasingly constructed in bits and the “informationist” knows that a sterile definition of information lacks the increasingly obvious need to represent cultural power dynamics and the intricate ambiguities of how people make meaning. What we need then, is some pragmatic framework that takes the best of each of these views.

This framework has been called New Librarianship, participatory librarianship, community-based librarianship, but for this talk, I will simply refer to it as knowledge focused. It is practiced throughout North and South America, in Italian cities, throughout the Netherlands, and is a major strategy in Australia and New Zealand. This knowledge approach defines a librarians using three facets:

- Mission,

- Methods, and

- Values

That is: the impact a librarian seeks, the means of achieving that impact, and the ethical framework that shapes the work of the professional. As we will see, any one of these facets is insufficient in defining a librarian, but each facet helps us answer those starting questions. I’ll begin with a mission.

The mission of librarians is to improve society through facilitating knowledge creation in their communities. This can be simplified as “librarians seek to help their communities make smarter decisions.” There are three things I need to point out in this mission.

The first is that it is grounded in communities. A librarian seeks to serve. Call them patrons, or users, or customers – a librarian uses his or her expertise to advance someone else’s achievement. This puts us in good company. A doctor is considered a good doctor not in what they know, but how they maintain the health of a patient. A lawyer is only as good as the wellbeing of their client.

For our purpose we will define a community as a group of people consciously linked by at least one variable (where they live, where they work, what interest they might have) and as important, but often unmentioned, a system for distributing scare resources (money, land, time, prestige). The consequence of linking our profession to the uniqueness of communities, means our own work must be tailored to the community. Where once librarians incorporated ideas from the industrial revolution to gain economies of scale through standardization (such as copy cataloging, common classification systems, and a common set of services) and a sometimes blinding drive toward efficiency, today’s librarians are seeking to adapt, not adopt, innovations into their communities. This leads to libraries as organizations looking and functioning very differently in differing communities.

The second point is where doctors help communities in terms of health, and lawyers in terms of law, a librarian helps their community through learning and knowledge. As an aside, this is why we need three facets to define a librarian, because our mission is not unique to us. Teachers and professors certainly share this mission. One could argue that publishers and even Google seek to improve communities through knowledge creation.

One last point on the mission. Knowledge is not a book, or a document, or a bit stream. Knowledge is a human’s understanding of their world. Knowledge cannot be written down, or copied, or transmitted intact. Books, documents, videos, these are all artifacts: the result of “knowing,” or a person using their knowledge. So when I say that a librarian improves society through knowledge creation, I’m not saying librarians store and provide access to artifacts. They may well do this, but those are tools to their real work – learning.

So if we seek to make our communities smarter, how do we do it? We do it through facilitating conversations. While we do from time to time lead classrooms, the core of the learning we participate in is inquiry driven. We support a community member (or indeed a whole community) learning. A reference interaction is a learning interaction. The catalog and interfaces we put in front of a community are systems that facilitate learning.

Why do I talk about conversation? Because that is the process we use to learn. This is somewhat borrowed from the humanist tradition, but is grounded in modern learning theory. When we are learning we are constantly engaging in conversations. With a teacher, or a friend, or an expert, or, most often of all, with ourselves. If you just asked yourself what I meant by that, you have proven my point. Called critical thinking or metacognition, we lead a rich internal dialog where we connect new information into how we understand the world to expand or correct our knowledge.

How do we facilitate this learning? In four ways:

- Access: providing access to conversations and resources.

- Knowledge: building up the knowledge of community members in order to participate in conversations.

- Environment: providing a safe intellectual and/or physical space that encourages learning.

- Motivation: providing internal or external awards to encourage or reward learning.

Once again a few things to note. With access, this is access to knowledge as well as documents and data. It includes access to others, meaning that a library connects people within the community. This is a participatory process and means that librarians must move beyond transactions to relationships.

Also note that a safe environment cannot be assumed for all members of a community. A library should be a safe place to access dangerous ideas. There is nothing inherent in library spaces that make them safe. That is an active process of community engagement.

Once again, the set of methods librarians employ is insufficient to define the profession. Mission and methods together are also insufficient. We need one last factor: the values we inhabit in our interactions with the community.

The values of librarians evolved over centuries of practice. They represent principles that guide our work. We have already alluded to a few:

- Service

- Learning

- Respect for diversity

To these we add:

- Openness

- Intellectual honesty

- Intellectual Freedom and Safety

To this we can add a general embrace of rationality and a call for evidence.

So now we have a platform for us to answer our questions. It is in answering these questions that we add a healthy dose of reality and hopefully develop some practical approaches.

We have sort of shortcut. A group of international librarians and museum professional put forth a set of professional competencies based on these ideas. It is called the Salzburg Curriculum.

- Transformative Social Engagement: Librarians must be able to articulate the goals and aspirations of the community and then actively advocate for these goals. It is in these negotiated aspirations that we can define what “improve,” and “smarter,” from our earlier missions mean. And I use the word negotiate purposefully instead of identification. Librarians are members of the communities they serve, and therefore have a voice in shaping the desired outcomes. I also use the word advocacy purposefully. Librarians cannot simply wait to be asked for help, they must be proactive in seeking change and action on behalf of the community.

- Technology: Rather than look at this as a list of skills or technologies to master, this competency recognizes that technology will constantly evolve. Therefore, librarians must constantly be learning new technologies. What’s more, they must be learning them with the community – co-learning and modeling lifelong learning.

- Management for Participation (Professional Competencies): Librarians must be able to build and maintain a platform for learning and conversation. This means they must be good managers.

- Asset Management: We must recognize that the collections we may manage or beyond books and documents. Some communities require fishing poles, tribal gear, musical instruments. The idea is that when a community requires resources, librarians need to be able to maintain them on behalf of that community.

- Cultural Skills: Communities are cultures – they have norms, languages, traditions, inequities, and histories. Librarians must be able to analyze and function within these unique cultures.

- Knowledge, Learning, and Innovation: Librarians are always learning with the community.

So finally let’s come back to the original questions I was sent and see if we can get some real answers:

- What technological expertise should librarians have?

To build/support a platform for facilitation online: access, knowledge, environment, motivation. This ties to traditional areas such as classification, metadata, but also includes knowledge of instructional technology, and information and technology policy. To evaluate technologies with our values in mind. Where once we audited databases for the use of Boolean queries, set creation, and item searching, today we need to assess how technology affects community privacy, enables transparency, and supports intellectual freedom.

- What should we leave to other professions?

In terms of technology? Building, programming, and installing, while we retain expertise in use and innovation. However, the distribution of these will remain contingent on the needs and capabilities of the community served. Ultimately a librarian should see potential partners through shared mission, methods, or values.

- Generalist vs specialist?

A librarian is a professional that specializes in facilitating knowledge creation across all contexts. Specializations in the areas of metadata, archives, preservation, software, open access, making, these are developed in response to community aspirations. Librarians understand that knowledge comes not from the accumulation of information or data, but rather reducing noise and identifying relevant context to make a decision.

- What does knowledge organization mean in 2017?

It is focused on knowledge and meaning over form. It means librarians adapting services, technologies, schema for a community context, not seeking universal solutions for all. It seeks to organize not only things, but to mobilize people and communities to make better decisions. It recognizes that everyone, every person, sees the world differently, and it is the role of the librarian to weave together a common fabric with the diverse perspectives.

The goal of librarianship was never to accumulate all the worlds documents, or information. It was to capture what was needed to advance the aspirations of a community. In these days of exponential growth of data stores, an incredible diversification of media, and, frankly, a dissolving common social fabric, librarians are more necessary than ever.

Well stated, Dave. In times past educators used to “short form” the curriculum as “books, bodies, buildings” to which was added “bytes”. Too many focus today solely on books and bytes (information) believing that only those who want to work in libraries (bodies, buildings) want to be “librarians”. But surely librarianship is the profession, regardless of where it is practised or under which title. “Information” is not a profession as much as “information professionals” wish it to be. Indeed, the “information professions” (plural as it is used) comprise several professions of which librarianship is one, as much as some try to harmonize them. Interestingly, the only ALA core competence (and mentioned in your post) *not* represented in most LIS programs by a tenure-track position is management and leadership, in some ways the most critical of all in the longer term.