This week the scheduled Real Time sessions ended at librarian.SUPPORT. While it wasn’t intended to, the series of discussions and presentations really sparked some ideas for libraries moving forward. I suppose it was inevitable as we started with Matt Finch talking about scenario and foresight planning. On the Real Time session with Sari Feldman, Hallie Rich, and Galen Schuerlin we talked about advocacy and connecting to communities in a time of pandemic. As part of that we had a little discussion of the phrase “The New Normal.” It’s a phrase that’s right up there with “in trying times like these,” in the “speed to cliché.”

We were noting that it is almost always presented in a negative frame. That is the new normal is expressed as what we will lose – loss of jobs, loss of budget, loss of human contact, etc. But what if we looked at in the positive frame…what is it that we want to be normal after this pandemic? We all acknowledge that things are going to change, I feel an obligation and an urgency to shape that change.

What is our agenda as librarians and the libraries we run on behalf of our communities?

Before I list my proposed items for that agenda, I ask a favor: keep reading. I want to explain where these come from, but more importantly, why having an affirmative and proactive agenda for libraries is vital. This cannot be about trying to predict where things are going to shake out and then running to show our value in that world. It has to be about librarians fighting for social change based on our fundamental and enduring values. There is no doubt that the “how” of libraries will change. I feel now (prepare for another cliché) more than ever the “why cannot.”

I will also emphasize that this is an agenda for the impact libraries should seek collectively. That is, it is not an agenda for how we run or operate libraries (though there will be obvious impacts). This is an agenda for libraries to work toward for a new normal in our communities. How we get there (open access, improved working condition for library workers, new standards for library science education, etc.) is vital and important, but I feel separate.

As one example, we must lobby and work toward universal broadband. This comes from our enduring value of access to information. Yet the pandemic has shown us that the way libraries to this point have worked for universal access, that is by being internet points of connection with WiFi in our facilities or loaning out cellular hotspots is no longer enough. We have to leave our buildings and ensure real national resources and policy is in place so our provision of the internet in the library is completely irrelevant. A big change to how, but not to why.

So what do I see as an agenda for a New Normal that libraries must work toward?

- Universal Broadband: Sheltering at home and closing schools and libraries has demonstrated that the internet must be a utility and available to all. The digital divide is wide, unjust, and the damage it is causing in this pandemic age is only highlighting the ongoing damage lack of access has caused for decades to rural and low income families and citizens. Some things to work toward:

- Classify and regulate the internet as a utility

- Build out rural access to broadband, including transforming libraries into Internet Service Providers

- Remove data caps

- Restore network neutrality

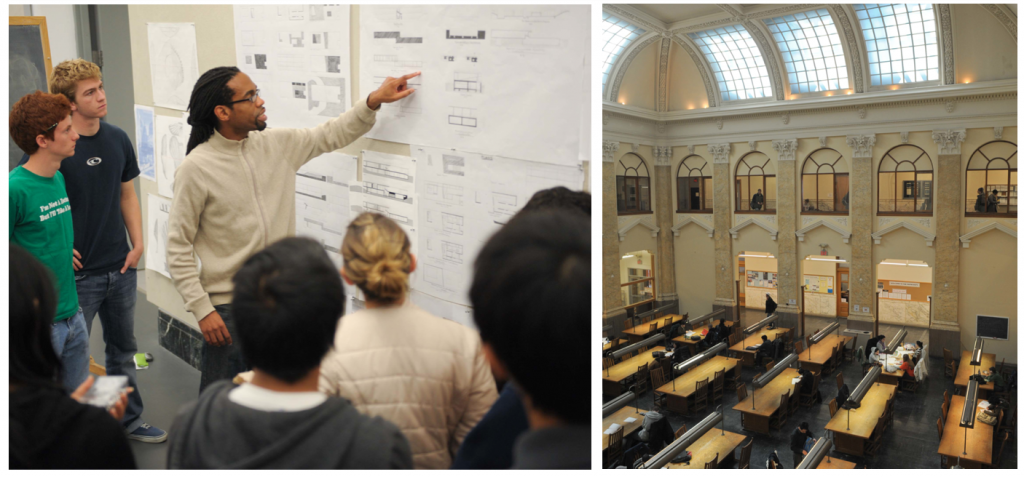

- Workforce Development and Training: At no time in our history have so many people been out of work and the unemployment rate rivals the Great Depression. While we all hope that will change rapidly once lockdowns have been lifted (though that will take many months to complete) there is an acute need now to support people looking for jobs and re-skilling. Libraries must work with higher education, other government agencies, and the private sector to not only get people back to work, but help people find a place in a new knowledge economy.

- Deploy adult education services like high school equivalency

- Ensure certified school libraries in K-12 schools to ensure literacy skills needed for vocational education as well as college preparation

- Team with higher education to support online learners in physical spaces

- Provide single service access points to government workforce services

- Provide permanent addresses and registration services for social welfare programs

- Develop strong prison library services including transition to community connections

- Expanding Voter Access to Democratic Participation: Voting is crucial to a well-functioning democracy but is insufficient for a healthy democracy (representative or direct). Eligible citizens must have access to the ballot and access to information on the issues and candidates they are voting on. They must also have transparency in the working of government at all levels to ensure it is the will of the people (all the people) being carried out. Libraries should be a safe place for contentious debate, and facilitators of a community dialog about the future and greater good.

- Develop active voter registration and identification services

- Host public forums on key community issues

- Develop and maintain community strategic priorities

- Ensure the Health and Well Being of Our Communities: In the immediate future, librarians must be key partners to public health in developing contact tracing efforts. The goal of contact tracing shouldn’t just be about surveillance, it must be about service. Librarians have not only a background in collecting and organizing information, they do so in a principled way that values privacy and is devoted to service. Librarians have a trusted relationship with their communities. When someone is sick, it is not just about finding out who they have been in contact with, it is keeping them home which means access to food and the outside world. Libraries cannot only track the infected but provide comfort and support.In a longer-term libraries need to form tight partnerships with mental and physical health agencies to guide community members to needed resources.

- Provide service-oriented contact tracing services to town, county, and state health departments

- Form partnerships with physical and mental health services and partners

- Provide forums highlighting wellness programs and ensure such programs protect community privacy

- Essential Crisis Response Capacity: In hurricanes, flooding, and civil unrest libraries have provided vital services to communities (academic, school, public, special, all types of libraries). The same must be true in this pandemic where our buildings cannot be a refuge. This pandemic has shown that the essential things in a crisis are food, water, medicine, and information.

- Build in emergency provisions to the copyright law to allow for rapid research access to relevant scholarship on a crisis topic (virology for example) and continued education services to home bound citizens

- Build citizen information services that not only disseminate trustworthy information on a crisis, but verifies the information and provides community feedback to decision makers

A few notes on these goals before we proceed. Libraries cannot achieve these goals alone. They all require strong alliances with government, industry, not for profits, and citizen participation. These may be part of our New Normal Library Agenda, but they are for the betterment of communities, not advancing libraries. While these are not ideological, they are political, and we should not pretend to be neutral in our goals. The right and the left can argue about how we achieve universal broadband (government policy like eRate or market forces and competition), but we must demand practical approaches to getting it done. The market has gone so far in say universal broadband, but as we saw with rural electrification in the Great Depression, government has to step forward. Lastly, these need to be done in alignment with our professional ethics – striving for diversity and inclusion first and foremost.

Being Proactive

In 2014 I wrote a piece on the dangers of libraries, public libraries in particular, expanding their missions too far to meet the needs of a community. We can’t be a single institution making up for all the inadequacies and inequities of our communities or nation. Now, as when I wrote this, more and more government services are retreating from the public sphere. Physical offices and real people on the phone have been replaced by automated phone trees and websites. Libraries, in many cases, have stepped in to try and provide service.

Librarians now must answer questions on tax preparation, the census, employment support, and a host of government services. All too often we stretch tight resources ever farther, and risk being a place to answer all questions…poorly. We must partner and advocate to fill these gaps. To build strong partnerships, we must be clear on what we value and what we contribute.

Effective librarianship means acknowledging our strengths and what we bring to the table. It also means advocating for the well-being of our communities beyond our doors and functions. Health information is not just the role of medical librarians, it is the role of the library to bring the health department with community health advocates. Why health and not just focus on “knowledge and learning?” Well, as is clear from Maslow’s hierarchy, people are not able to lean if they are scared, hungry, and sick. To ignore the need to keep people healthy, our mission on learning and community is hollow. Public libraries are not viable institutions if the community is unemployed and without taxes. We have seen this clearly in the English libraries where volunteer libraries have repeatedly demonstrated the need for professional librarians and real budgets. In effect to protect our self-interest, we must protect our communities.

Libraries can no longer pretend we are apart from the full spectrum of needs in the community, that we can remain neutral in the face of inequity that divides these communities, nor can we pretend that we can be the fabled savior acting alone to save communities…we are our communities. Librarians are citizens, voters are stewards of collections, experts are part of our true collection. To say we are about literacy and not partner with teachers means our dedication is to what we do, not what needs to be done from the perspective of the community. To say we are about community and only be a source of ebooks in a pandemic is hypocrisy. Yes, our fellow citizens need ebooks, but they need compassion, connection, and community dedicated to their full well-being.

A new normal is coming. Will this new normal be founded on what we lost, or what we seek to gain?

In the dark ages of European history, people lived literally in the ruins of the Roman Empire. Every day as they sought to survive disease, famine, and violence they were reminded of what they no longer had. It paralyzed societal development. It took a renaissance that respected and learned from the past, but confidently (and yes arrogantly at times) was dedicated to moving forward.

Will our new normal be libraries half empty by social distancing, or community hubs that extend beyond our socially distanced footprint to the kitchens and living rooms of every one of our community members? Will we tell of the time when we provided internet access in our buildings to over 90% of US citizens, or will we tell the tales of how we won with our allies universal access for all? Will we wait for a vaccine as our staff gets furloughed, cars park in our parking lots for WiFi, and we endanger our most valuable assets, our staff, in curb side drop offs? Or will we partner with departments of health, technology companies, and foundations to ensure disease is tracked and the sick are cared for?

We must fight for a new normal with our collections, our buildings, but mostly, with our expertise. Librarians by title, by education, or by spirit must bring about a new normal that pushes ahead society. It must minister to those seeking meaning. It must support better decision making in the wake of this pandemic and in preparation for the next crisis.

I am making this document available for comment on Google Docs to see if we as a community can refine and improve it. Please join the conversation at: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1z4urUctLkAf7yYmQt5SOVf1tmJTnbmz2_BoXWms1KTA/edit?usp=sharing

Thank s to all who took the time to add comments. They are extremely helpful. I’ve turned off commenting for now so I can incorporate them into a version 2.