“Never Neutral, Never Alone.” Transforming LIS education for professionals in a global information world: digital inclusion, social inclusion and lifelong learning IFLA Satellite Conference. Vatican City (via video).

Speech Text: Read Speaker Script

Abstract: Library science is getting harder to teach. The variety in libraries of all types is increasing as more and more mold themselves to their communities rather than field-wide norms. How can library science education change to meet the new variety, and the variety in a post-neutrality world.

Audio:

Never Neutral, Never Alone

August 22, 2019

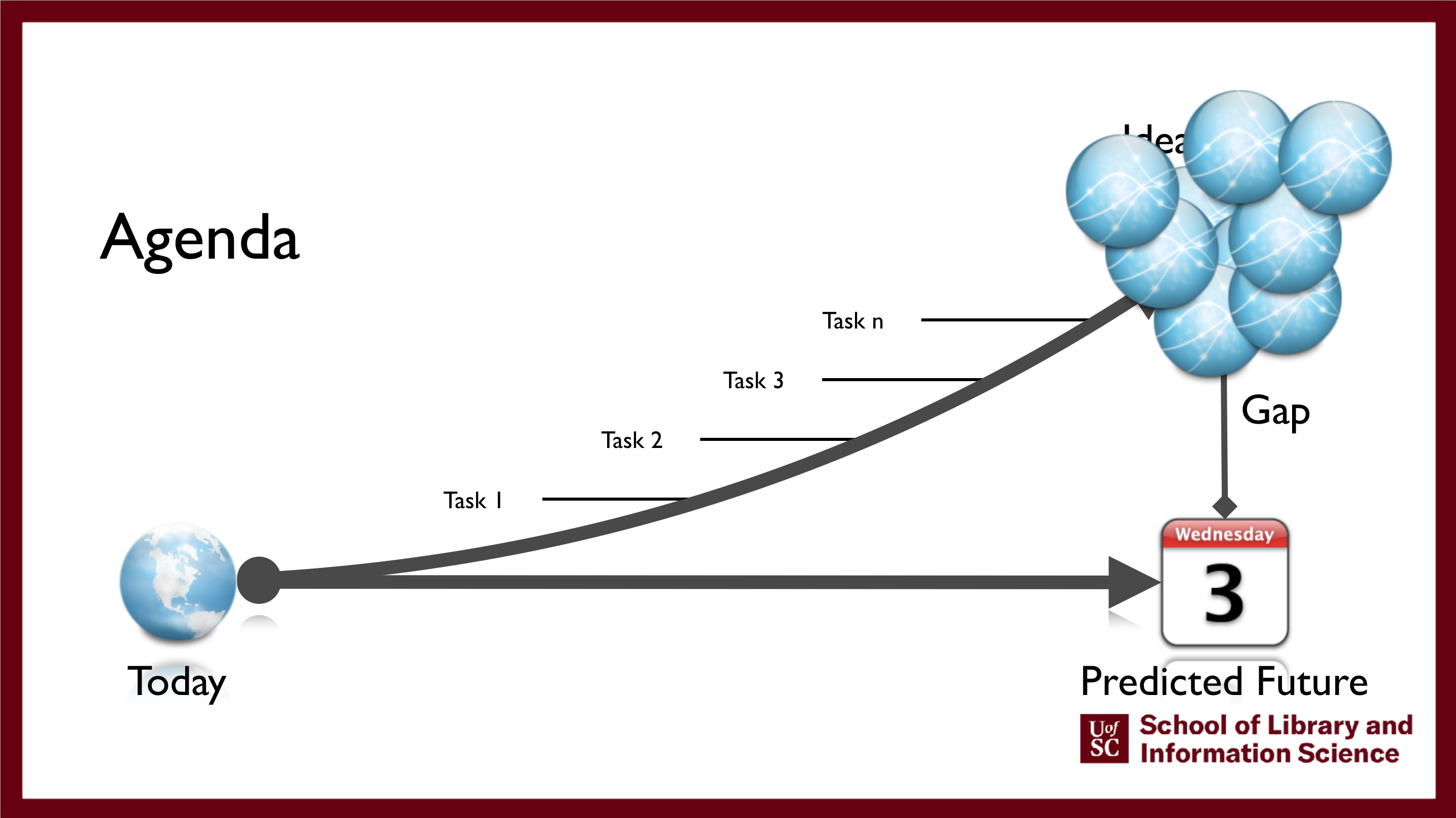

It is time to have a frank conversation about LIS education. The problems with how we prepare librarians are often phrased as a gap between theory and practice. The argument goes that library schools are not producing graduates with a real-world practical skills; instead focusing on generalities and theory. This is a perennial argument, and if there was a library school in ancient Greece, I’m sure Dewey’s Socratic equivalent would be criticized for not preparing students to argue effectively in a marble building as opposed to a brick one.

This theory/practice gap, however, is not the real problem. The real problem is that no one knows what new librarians need in the second year of their career, much less their 25th. There is no common entry point, because there are fewer and fewer commonalities between libraries. As libraries of all types are organizing themselves around the local needs of a community – be it a town or a university or a school or a hospital, the differences in working environments for librarians is changing not only quickly, but diversely. What once was applying a standard set of reference skills to an owned set of databases, or applying cataloging skills to local classes and codes, is now about community outreach librarians knowing the unique culture of a city, or a user-experience librarian learning the realities of undergraduates in a particular school at a particular time.

The libraries that we hold out as global exemplars like Dokk1 in Aarhus, or LocHal in Tilberg, or San Giorgio in Pistoia, or the libraries at University of Michigan or there at the Vatican with its petabyte data center and global digitization initiatives are as diverse as they are impressive. No one school can prepare all starting librarians for all libraries. This doesn’t even consider the inclusion of archives, special collections and research services that are not even connected to traditional library institutions.

The standards and competencies we develop will continue to become more general, and more focused on lifelong learning and community engagement areas. Where once we could define cataloging skills down to the standard, we now must recognize that information organization can take the form of MARC, RDA, FRBR, Dublin Core, or just general concepts of the semantic web. Theories of classification still apply, and still must be taught, but the specific skills that accompany these skills are now purely illustrative. Where once we taught reference as a series of genres like atlases, and encyclopedias, today we teach learning theory and pedagogy. These are important areas to teach, but they will never meet the mark of first year practical skill.

Before I jump into thoughts on addressing this situation, let me say these are good problems to have. The reason there is no canon of skills is that librarianship is a vital and dynamic profession. The reason there is so much diversity in the field is because the need for librarianship is growing. The communities we seek to serve are becoming more diverse and varied because we are at least attempting to go beyond real barriers of class and race. If all we were doing was preparing spare parts for a handful of libraries that hadn’t changed in decades, our stable and satisfying curriculum would be the surest sign of the impending death of libraries.

No, the answer is not to try and develop a single standard for all, but to create continuous systems of learning that are agile, connected, and embedded. The library education of tomorrow, and increasingly, today, must smash the divide between the “real world” and the “academic.” It must also break the idea that one degree at the outset of a career is sufficient preparation for an entire lifetime of serving a community. Lastly, it must also fully embrace that we are preparing librarians, not library workers. And accept that librarians are not neutral, and must develop skills that are as much about resilience and self-examination as they are about how to run an organization.

Let me take these ideas in turn. I’ll begin with agility. What is an agile system of library education? It is one that is constantly seeking out not only best practices in librarianship, but innovative ones. It develops a curriculum and means of delivering that curriculum that are flexible and can be deployed quickly. One example of this is in Norway where the Akershus University College of Applied Science’s Department of Archivistics, Library and Information Science holds a biannual conference for its alumni and other librarians. It is a chance to not only bring in the latest thinking from the field, but to connect and listen to graduates and what they need.

At the University of South Carolina, we are pairing every library science degree with a specialized certificate that documents areas of focus such as data science, health information and so on. However, we have structured the certificate so that the specialties can change from year to year. We see students getting certificates in artificial intelligence and librarianship, library construction and design, and service to refugee populations. The list of specialties will be long and change year to year, student to student, as the world these librarians seek to serve changes.

Which brings me to my second new “standard” for library science education – connected. I would love to say my faculty represented hundreds of specialists all expert in the latest develops in the field. They do not. They are scholars with specialties and a broad view of the field, with an ability to connect practice with larger concepts. However, our alumni and the institutions they work for, and that we partner with, do represent hundreds of specialists developing and deploying innovative services in communities across the globe. Library schools must be a part of creating a network of libraries directly engaged in the education of new librarians.

This goes well beyond a set of adjuncts who teach a few classes, or internships, or field trips. We must develop a network of libraries that share both in the responsibilities of education and the funding of such systems. The library science school of tomorrow is truly a hub that delivers a core of library concepts and research skills, and then connects students with developing innovations in the field. Your faculty may be on the tenure track or working the reference desk. Your mentor may have the tile of professor, or librarian, or archivist, or programmer. The hub ensures rigor in the learning, but more importantly ensures cohesion in a student’s degree.

The dynamism in the library profession can be clearly seen in the enormous offerings of professional development. A librarian could spend a week just sitting in webinars and online workshops in just about any aspect of the library profession. Our library associations, our vendors, our universities, our publishers, our libraries are in the midst of an amazing creative rush of developing online education. However, there are no real attempts to coordinate and link all of these together into a coherent understanding of the field. Faculty in the library school of the future will spend as much, if not more time evaluating portfolios of these diverse online resources as they do teaching classes. The days when the expertise of a field was contained within a single library school are gone. The days when the totality of library expertise could be represented in a single faculty are gone.

We must look to other models of how we prepare professionals, hence, “embedded.” That network of libraries and expertise we build must also be seen as places for residencies where we embed students for direct, contextualized learning. The advent of online education has made place irrelevant in many of our programs. You no longer have to move to Columbia to get our degree. However, in making this shift, we have also lost the power of place. We must now join the power of place with the flexibility of online.

Students will no longer move to Columbia because that’s where the faculty are, they will move to Aarhus, and the Hague, and Taiwan, and Charleston because that’s where innovative practices are being formed. Taking a page from the medical residence, we are turning our network of partners into residency opportunities for our students. Libraries can use these residencies to attract the best new librarians to job openings, and the students gain authentic specialized knowledge on top of the core we provide. And hosting these residencies is an opportunity to expand the learning of the students to the learning of the whole organization.

In Charleston South Carolina, the local school district pays for 10 in-classroom teachers to get their master’s degrees and become school librarians. The funds for these cohorts are then re-invested in the school district. The tuition of the students pays for national speakers, onsite workshops, even open course development that are provided to the entire district. This creates a sustainable means of continuous library education well beyond the granting of a degree. By enrolling 10 teachers, the district enrolls the whole district in library school.

And what are these students learning in their residencies and in the network? They are learning to be librarians. Not people who work in a library, but a set of values, research skills, and a mission they will take with them to jobs in libraries, or the technology sector, or the banking sector, or government. They will be going into these libraries, and businesses and governments a point of view. They are not neutral deployers of skills, they are professionals on a quest to improve communities through learning. They will go not as parts of a system, but as advocates for inclusion, privacy, access, and openness.

In order to prepare these librarians, we must develop a curriculum of self-reflection and analysis. We must address, in the curriculum, self-care, vocational awe, resiliency, and self-awareness. These are not soft skills, but techniques that allow our librarians to assess, engage, and adapt to community needs and realities. It is no longer acceptable that we send out librarians into communities prepared to answer reference questions, but unable to process the poverty they may find there. It is no longer acceptable to train academic librarians to recognize gaps in the collection, but not to recognize student homelessness. It is no longer acceptable to train archivists who do not understand the politics inherent in controlling the memory of a community.

Analysis cannot be limited to the individual and introspection, however. Methods of analysis – of research- are necessary. No matter the environment our new librarians find themselves, they will need to know how to understand a community, how to assess services, how to collect, analyze, and protect data. Participation is a goal, and we shall never know how well we are matching that goal without instruction in research methods – instruction that is embedded in real communities with real questions, and contextualized methodologies.

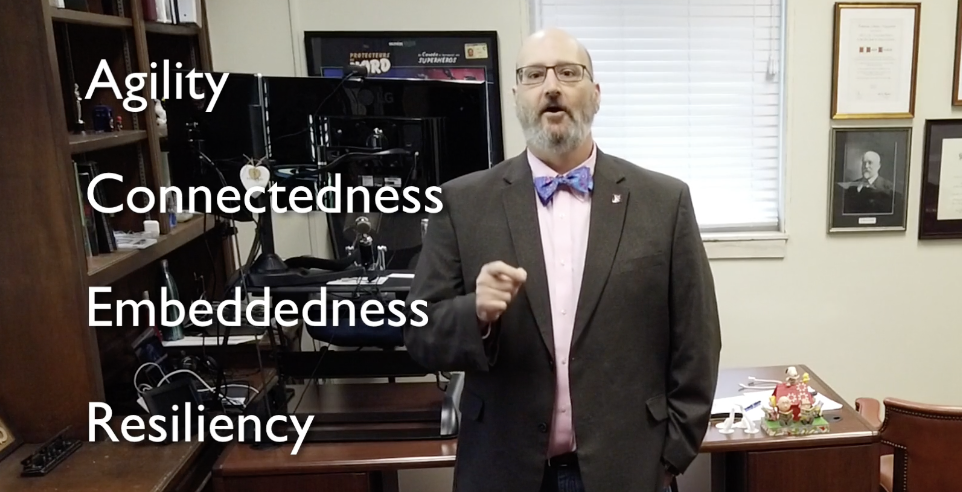

And so these are my new metrics for evaluating the effectiveness of a library science program:

Agility – what ongoing methods are in place to identify, evaluate, and prepare students for developments in a rapidly changing profession?

Connectedness – who are the partners networked with the program and its faculty to ensure direct connection of the classroom to the field?

Embeddedness – what are the program’s ability to deliver authentic field experiences to students that allow them to contextualize theory and research methods?

Resiliency – how prepared are librarians to face, understand- that is analyze-and solve the problems in a community in line with the professional mission and values of librarianship?

Today the librarians we prepare are building makerspaces, they are crunching masses of data in civic redevelopment projects, they are saving tweets for posterity, and housing masses of research data. Our graduates are delivering knowledge and food to rural communities left behind in an information economy. They are supporting the research of Nobel laureates and citizen scientists fighting for clean drinking water. They are fighting for access to the world’s knowledge in developing economies and bring dignity to marginalized communities. They need a strong platform to prepare them for this work and then support them throughout that work. Library science programs can be that foundation, but not alone. We must connect the innovative librarian stifled in a large bureaucratic library with an innovative librarian revolutionizing a small town a continent away. And connect them both to scholars and the means for continuous learning.

Library schools are a vital part of the reinvigorated library profession. Yet, just as we have seen the road to success for libraries is in adapting to and including the community, so too must our schools become open platforms orchestrating participation and adapting to the community of our alumni.

Thank you.