Comments to the South Carolina Library Association. Greenville, SC. (via video conference)

Speech Text: Read Speaker Script

Abstract: South Carolina Libraries can help lead the world and help save it.

[This is the script I used for my talk.]

Today I am going to ask you to save the world. But that seems like a kind of heavy place to start, so instead I’d like to start with cancer.

There is a reason I’m not there in person, and a reason I have not been coming to visit your libraries recently. You see I am in confinement in Durham, North Carolina. I realize that sounds like I’m in prison – which might not surprise some of you – but confinement is actually a medical term.

In an attempt to rid me of cancer on August 24th my son donated nearly a liter of his bone marrow to replace my own. For the past 60 plus days I have been confined in Durham with daily visits to the Duke Medical Center for treatment. There were plenty of difficult days where just getting out of bed was a success. Daily transfusions of blood, 21 pills a day, and a white blood cell count of 0 can really take it out of you. But, I’m getting better. As I get better, I’m finding Netflix a bit less entertaining, and it turns out that I really hate jigsaw puzzles.

So my mind turns back to the world. It would be easy to find another series to binge or another book to read, but the world intrudes on any oasis after a time. I promise this talk won’t be a political venting. But it is impossible, no matter your politics, to see the stress and strife in the world. Issues of immigration, opioids, embolden racism, and a desire to pit us versus them seem to be a pandemic.

Between the nightly news and the overwhelming article sharing on Facebook – Facebook which seems to be in a race to get rid fraudulent voting information and leak our personal data-it seems we are entering into a new cold war with Russia, or China, or apparently a cold civil war. Twitter is toxic. The blue wave is coming or it will be overwhelmed by a red wave. Every commercial on Durham television after 6 is one politician bashing another. And don’t even get me started on the Pete Davidson/Ariana Grande split.

[Play Ghostbusters Video]

OK, that might be a bit over the top…but not so much for everyone. My point is that our communities are divided and under stress. Yuval Harari, the author of books like “Sapiens,” talks about this in his latest book “21 Lessons for the 21st Century.” He contends that the world organizes around huge narratives. Before World War II it had three to chose from: fascism, communism, and liberalism. By the way, liberalism as in liberty or more precisely liberal democracy – that’s us in this picture. After the War there were two: communism and liberalism. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, just one.

And now, too many of us see liberalism falling apart, or so Harari argues. When we are without some large guiding narrative, big questions become impossible to answer with consensus. Why do we fight a war? What is the purpose of our foreign policy? What is the American Dream today? And without a common narrative as a people we are regulated to us versus them, camps over countries, and personal gain over community advancement.

Now even if you don’t fully buy into Harari’s argument, there is a real danger of a people, community, and yes, domains, when there is no large scale narrative. I see this in an example from history. It is an example that looks at how without a working narrative a once well-respected profession was increasingly seen as obsolete – their tasks able to be learned by everyone not just professionals. The education of this discipline was stagnant, emphasizing theory and concepts over real application. It was a profession with service at its core and had existed for thousands of years.

The discipline I would like to talk about is medicine.

One of my favorite books of all time is John Barry’s “The Great Influenza.” Barry writes about the great swine flu of the early 1900’s. But it really tells the story of the rapid transformation of medicine from an art to a science.

Today we hold doctors in high esteem. We see the field as essential and specialized. Yet that was not always the case, particularly in the late 1800’s. Here are just a few excerpts from Barry’s book to paint a picture:

“Hence Oliver Wendell Holmes, the physician father of the Supreme Court justice, was not much overstating when he declared, ‘I firmly believe that if the whole materie medica, as now used, could be sunk to the bottom of the sea, it would be all the better for mankind-and all the worse for the fishes.’”

“…in 1835 Harvard’s Jacob Bigelow had argued in a major address that in ‘the unbiased opinion of most medical experts of sound judgement and long experience…the amount of death and disaster in the world would be less, if all disease were left to itself.’”

These opinions and ideas also had more direct consequences, that may sound a bit familiar. First in professional education:

“Charles Eliot…had become Harvard president in 1869. In his first report as president, he declared, ’The whole system of medical education in this country needs thorough reformation. The ignorance and general incompetency of the average graduate of the American medical schools, at the time when he receives the degree which turns him loose upon the community, is something horrible to contemplate.’”

Then in the reputation of the professionals themselves:

“As these ideas spread, as traditional physicians failed to demonstrate the ability to cure anyone, as democratic emotions and anti-elitism swept the nation with Andrew Jackson, American medicine became as wild and democratic as the frontier…Now several state legislatures did away with the licensing of physicians entirely. Why should there be any licensing requirements? Did physicians know anything? Could they heal anyone…As late as 1900, forty-one states licensed pharmacists, thirty-five licensed dentists, and only thirty-four licensed physicians. A typical medical journal article in 1858 asked, ‘To What Cause Are We to Attribute the Diminished Respectability of the Medical Profession in the Esteem of the American Public?’”

So what changed? Medicine developed a new narrative: one based on direct scientific observation. One that placed experimentation and sharing what works above grand theories developed centuries before. Doctors began listening to their patients. Doctors began using chemistry to develop first antiseptics, then anesthesia, then antibiotics, then a host of pharmaceuticals.

Note that the advances to medicine were not easy, straightforward, or strictly ethical. Core gynecological practice was developed with unwilling and anaesthetized slaves. The chemotherapies that were used to treat my cancer were developed from chemical weapons first used in World War I and later through exposing black service men to mustard gas…by the U.S. Army. But medicine is coming to face those ugly realities and developing codes of ethics that are inclusive and enforced.

And so we come to librarianship. A profession that too is adopting a new narrative. A new librarianship that is focused on our communities and the needs of people – not customers or users, but people. And in my confinement I begin to see stories globally of libraries that are not paralyzed by a growing nihilism and not building walls to be oasis and sanctuaries ignoring the concerns of the world around them. They, librarians, are building community hubs and services. They are taking the new narrative of librarianship – one based in both knowledge and action – and healing communities.

I read, for example about Glasgow Libraries in Scotland. They have teamed with a non-profit, Citizens Advice Bureau to directly address homelessness. They not only located experts in homelessness in the libraries, they train library staff to identify and approach the homeless as well. Then the librarians and Bureau staff work together to provide counselling, support and advice to people affected by homelessness.

I first became aware of this idea of public libraries serving as the functional local government from Gina Millsap, director of the Topeka Public Library. Kansas has become notorious for not having a functional state government as the legislature sits in opposition to the governor. This hasn’t stopped Gina and the librarians of Topeka from helping their citizens. They received an award when they set out to tackle illiteracy. They trained librarians in basic literacy instruction. When it became clear the neighborhoods in the greatest need of service was too far from the physical library, they worked with the city bus services to change bus routes. Then they sent librarians into those communities. When demand for the service became too great for the librarians the library trained hundreds of volunteers to work throughout the city.

The idea of libraries becoming direct civil service for their communities can also be seen in Cuyahoga, Ohio. The public librarians work in the local prisons. When it became clear the prisoners didn’t have enough education materials, the library teamed with Overdrive to fix tablets for the incarcerated. When a prisoner was set for release, the librarians set up appointments with their local branch librarian who would help them with housing and other social services. And speaking of prisoners, in Brazil the incarcerated can now read down their prison terms – 4 days for each book, 12 book a year.

I see a narrative of community support and learning in Narcan projects that prepare library staff to deal with opioid overdoses. I see programs, like the recently announced health insurance enrollment initiative of the Public Library Association. Bookmobiles converted to maker spaces to reach rural populations. Smart citizen initiatives across the European Union that demonstrates that there are no Smart Cities, without smart citizens trained in data-centered algorithms that can liberate and oppress.

I also see it very much in South Carolina. I see it in Richland with the difficult conversations where librarians facilitate community dialogs about race. I see it is Spartanburg where librarians are preserving history and making it accessible to their community members. I see it in Union with expanded facilities. I see it at the State Library where they are working with librarians of all types to accommodate people of differing abilities. I see it across South Carolina. Libraries that became areas of refuge and rebuilding in hurricanes and thousand year floods and respond to the horror of racial killing.

I also see it beyond public libraries. Academic libraries are teaming together to preserve the unique histories of communities. College libraries that have started to take on the reality that a number of college students become homeless trying to afford tuition.

Across the globe as politicians argue about immigration, librarians are going to resettlement camps to offer materials, and education, and hope. Librarians that turn citizen anxiety into voter registration drives.

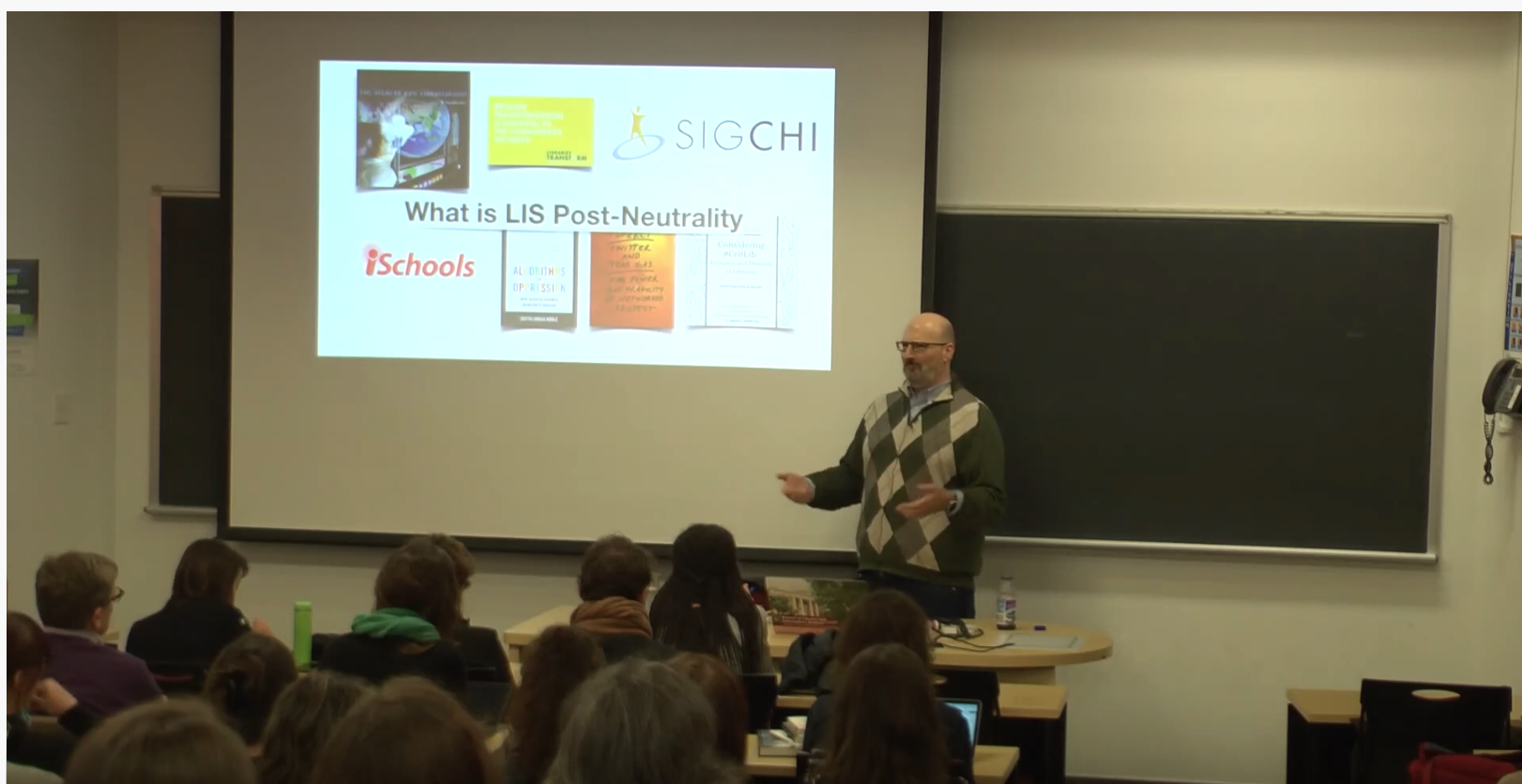

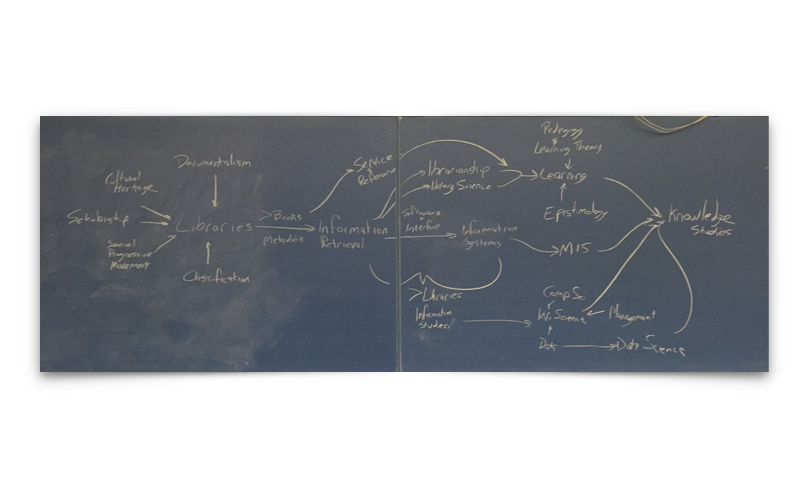

In essence I believe that librarianship has passed from a sort of professional nihilism where we were going to be displaced by Google and Facebook and Wikipedia to a renewed mission to improve society through inspiring learning in our communities. And while this new librarianship, this new knowledge school of thought, is far from universal, it is growing and having a positive impact here in South Carolina, and in Germany, and in Uganda, and China, and Brazil.

This is far from the first time libraries have played a pivotal role in reshaping society. The librarians of ancient Alexandria were close advisors to the kings and queens in Egypt. Librarians kept ancient lessons available to the scholars of what is now Korea and China. Large libraries in the Muslim cities of the Iberian Peninsula helped advance architecture and mathematics and would eventually be the fuel for the Renaissance.

The libraries of Oxford and Cambridge fueled both the enlightenment and the industrial revolution. And those doctors who in the 1800’s found themselves on the verge of collapse? Today medical librarians are supporting the very team that is keeping me alive.

And so, I come back to my opening line. I am here to ask you to save the world. I am asking you to take the new narrative of knowledge and meaning that is displacing the old narratives of efficiency and access to information and spread it beyond your walls.

To be clear, this is a lot to ask.

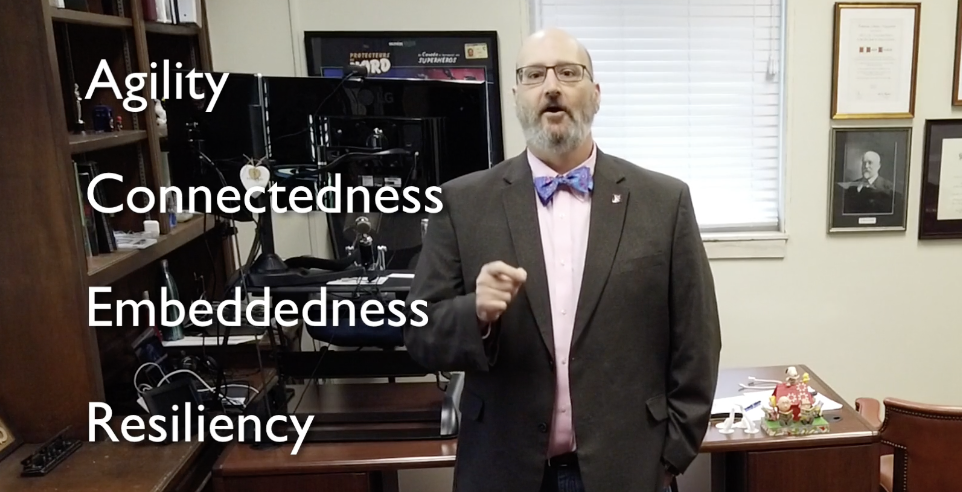

Gone are the days when every library looked and acted alike. For while we are united by a single mission, how our communities make that vision a reality will be different. The mission of a librarian is to improve society by facilitating knowledge creation in his or her community. Or put more simply, our job is to make the lives of the people we serve, be they parents, lawyers, seniors, professors, gay, black, educated or not, to make their lives better and more meaningful through learning. Learning happens with the pages of a good novel, a comic book, hands on in a maker space, and talking online.

Your job as a librarian is not to offer everything – maker space, Narcan, prison liaison – but those services that best help your community reach its highest aspirations. Your job, as a librarian is to be an active part of a global network of librarians sharing ideas, experimenting, sharing results, and then working with community members to identify which ideas will work locally, and to adapt – not simply adopt – those ideas in your library.

You get collections that meet the needs and the demographics of your locality.

You get instruction and information literacy not based on some universal method – but that starts in local belief and ends in global awareness and is informed by rationalism.

You get engagement with industry and other local government based on the needs of the community, not simply opportunity.

You build smart cities with smart citizens who not only understand the potential benefits of technology and data, but the potential for oppression by algorithms.

You have my pledge that the University of South Carolina’s School of Library and Information Science stands ready to partner with you. We are teaming with libraries such as Charleston to develop new professional development opportunities for all staff. We have heard your worries about currency of curriculum and the fear of creating a sort of monoculture of thinking. We are currently remaking our curriculum as a knowledge school. And if you haven’t looked at our faculty in a while, take a look again. We have retained our best scholars and recruited a new array of amazing scholars over the past three years – nearly half the faculty is new.

I may be confined to Durham and home for this year, but the work of my school, and the work of building a global knowledge school of thought goes on. From Berlin, to Montreal, to Florence, to Mumbai to Columbia librarians are strengthening their communities. They are living up to the values of the field laid down over the past centuries: openness, diversity, learning, access, and engagement. Librarians in this state, this country, and across the world are putting these values into action within their buildings, and going out into the community. We are building strong local networks of schools, universities, businesses, non-profits, faith based organizations, and beyond to ensure every member of a community has the power to learn and find a place in that community. We librarians through SCLA, and ALA, and on Facebook, and in peer networks are connecting together a global corps of librarians and allies into the knowledge school of thinking.

Our communities are hurting, and bewildered, and dividing due to pressures of xenophobia, racism, economic disparity, and politicians who seek power above the greater good. We librarians, you and me, with our partners must tie them back together. We must model how even the most contentious debate can be conducted with respect. We must model how fake news is dispelled with knowledge, not picking a side. We must model that local government supported and overseen by the people, with the people, can be effective and powerful. We must model acting locally and globally for the common good.

Realize that in times of great uncertainty, people do not need a refuge walled off from the outside world, they need to feel empowered to effect that world. And that goes for you and you staff as well. Don’t tell me that your mayor or city council won’t let you, or the people don’t need it happen. In my very short time in South Carolina I have seen a library preserve signs and flags central to the civil rights movement. I have visited a library that was segregated well into the 1970’s now reach out across old mill towns to ensure that library service is available to all. I have seen a library team with a title I school and a Latino organization and the local city council to build a city-wide literacy effort. I have seen a county raise the salary of every worker in a library system to promote equitable labor practice. And I have seen an annual march on the capital by thousands of school children drawing attention to the importance of reading.

My fellow librarians now is your time. The need in our communities is great, but there is a resurgence of trust and funding in libraries. When you go home, bring your staff together and ask how can we convene the community and truly assess their aspirations and dreams. Connect together, not once a year, but every day. Build mentorship networks so no librarian ever feels isolated. Do this if you are in a big library or a small one. In a public library, or academic or special. Build the narratives of your community and celebrate it. Work with the county, and the hospital, and the pizza shop, and the tourist board.

My fellow librarians, let us now save the world.

Thank you.