“Expect More: From Change Agent to Advocate.” Congrès des professionnels et professionnelles de l’information. Montreal, Canada. (via video conference)

Speech Text: Read Speaker Script

Abstract: Society needs librarians who are non-neutral, proactive change agents.

With French Subtitles

[This is the script I used for my talk.]

Bonjour, je m’appelle David Lankes … and with that I will stop abusing your beautiful language.

Today I’m here to talk about being a change agent. I am also with you today to celebrate the translation of Expect More, a book I developed with libraries across North America to help change agents move our libraries and librarianship forward. I will refer to some ideas today that are explored in greater depth in Expect More and I hope you will become part of the conversations around the book and the field moving forward.

So what can I say about change agents? I could talk about things like the power of narratives. I could talk about the difference between innovation and invention. I could put up models of change, show the famous Everett Rogers Diffusion of Innovation distribution of early adopters to laggards. I could talk tactics like building a coalition of the willing and how to get the resistant on your side.

I could, and may, talk about those, but to begin I would like to tell you a joke, and then ask you a question. Here’s the joke:

An old professor of mine used to tell me Change is like Heaven…everyone thinks it’s a good idea, but no one wants to go first.

And this leads to my question. If you are preparing to be a change agent, what change are you preparing for? Many of folks who resist change are not stubborn or chronically cynical – they are unsure. We who seek change often have passion and enthusiasm, but sometimes lack the specifics needed for folks to evaluate and accept the change.

You see, that’s the problem with change. Many of us assume it is a positive thing. We talk about technological advances, not technological randomness – even though all of those advances at once can lead to extraordinary disruptions in our lives and communities. Yes, I can now transmit pictures of my lunch instantly to my friends, but at the same time thousands of people can now know where I am eating. I can email folks in the middle of the night with my great idea, but at the same time I can have a boss asking me how we are coming along on that great idea first thing the next morning.

And it is hardly just technology. Not even 5 year ago in the United States we were celebrating a Supreme Court decision that made gay marriage legal. Now we have a federal Department of Justice and Education saying that firing someone for being gay is legal, and trans students in schools have no protection.

Every year in South Carolina we graduate our new librarians in Rutledge Chapel. Rutledge was the first building that housed the South Carolina College – now the University of South Carolina. During the US Civil War, the building was used as a hospital for confederate soldiers. After the war it was opened up as a Normal School where professors of all colors trained freed slaves to be teachers.

However, once union troops withdrew and a new governor was elected he shut down the normal school and the college and re-opened it a year later for only white male students. It would be another 83 years until the university accepted another black student. I tell this story to our graduates to make the point that no change, not even a something so vital as a civil right is ever permanently won.

So, I assume that we are all here because we seek positive change in the library field. We want our communities, be they towns, or colleges, or businesses, to be well served.

But of course, that is not enough to enact change. What does well served mean?

I am here to tell you that we can no longer answer that in the way that we used to. We must expect more out of ourselves, our institutions, and our communities. And in order to do that – we must let go of long held notions of the field.

The first idea we must move past is that librarians and the institutions we build and maintain are neutral. If we talk about positive change, if we talk about smarter communities, if we talk about improved service – we have a point of view. Even if we talk about quality – we must acknowledge that high quality is different from low quality, and that takes a judge or arbiter.

We have seen the narratives of libraries change over the past decade. No longer do we talk about libraries as collections, or libraries as access points. Today we talk about libraries as transformational; we talk about a library’s mission as center of a community, or even necessary to promote democratic participation. We point to studies of libraries as investments returning so many dollars for every number of cents invested.

This line of reasoning is not neutral. Democratic participation is seen as good – community building as a proper use of dollars, and return on investment as a useful metric. Decisions all.

After we acknowledge that we are not neutral – that we seek to do good, to make positive change in communities – we must know there is a difference between providing a community with what it wants and providing them with what it needs.

Now, this has always been the case and it has reinforced some of the worst parts of society when seen in retrospect. Carnegie built libraries because, in his opinion, the workers could not choose what was best for them. We segregated libraries in the United States to prevent civil discord. We kept fiction out of public libraries because it was not seen as educational. Libraries are products of their society’s failures as much as their successes. Even so, libraries must quest to constantly do better.

So today, libraries do not seek to become Amazon because we believe in the importance of privacy and the need to serve all in a community – not just those who can afford it. We fight against racism and intolerance because diversity and learning are core to our mission, and the richest learning occurs in the presence of the most diverse views. These values of transparency, diversity, and learning don’t just stop at the library door – they must become part of our mission to instill them in the community itself. To be a true change agent is not to serve a member of the community, but to empower that person to advocate for their own needs and aspirations. And when some sector of our community is unable to advocate for themselves – then we must be their activist.

An activist not just for literacy, or library funding, but for equity of access to opportunities and throughout the community. Activists for new citizens. We must not simply be a service to a community, but a voice for the power of equity and leaning within that community. I wrote in Expect More “The difference between equal and equitable? The same (equal) versus fair (equitable). Equal service to a community almost always means ideal service to a sub-group, and variable usefulness to every other segment of that community. For example, letting anyone in a community borrow books is equality. Providing Braille books to the blind is equitable. Book borrowing, equal, home delivery to the housebound, equitable.”

When the Topeka public library in Kansas identified readiness for school as a priority of the community, they sought to increase literacy in 4 and 5 year olds. When they found that the lowest literacy rates were in one urban neighborhood – a neighborhood of poverty – they worked to build a bus route to bring people to the library for free. When the community couldn’t make it to the library because of the demands of multiple jobs, the librarians went in into the community. When there was more need than the librarians could provide they trained community volunteers to take up the slack.

When the Cuyahoga County library in Ohio identified the horrible reality of prisoners being released without resources – leading to a huge rate of re-incarceration, they acted. They went into the prisons to provide job skills and education. When they found no prison libraries, they worked with partners to bring in tablets loaded with materials and learning software. Then they set up appointments for released prisoners to meet with their local neighborhood librarians who helped them with housing and job skills. When they identified that ex-prisoners were losing benefits like food support because they couldn’t find stable housing, they worked with the county government to allow local library branches to be their official homes and to check in with their library card.

In the streets of Toronto, librarians drive Internet enabled cars into needy neighborhoods. In other Canadian towns libraries operate needle exchange programs, or host health fairs for the homeless.

All of these innovations were put in place because librarians came together to define positive change and what communities needed.

And so we come back to being a change agent. What change are you seeking? I tell you now that changing the mind of the 30 years of service reference librarian who still believes that the library should be books and wants to bring back the card catalog is impossible if you try to do it one change at a time. The first thing you need, we need as a field, is a vision of librarians changing all of society. Without this big vision, every change will be seen as incremental, a fad, and something to be waited out.

We need a vision where we can articulate why a makerspace belongs in some libraries, but not others. A consistent vision that talks about why some libraries need more stacks, and some need fewer. In essence we need a cohesive vision of the field that allows librarians to build libraries that are responsive to the unique needs of their unique community, but still part of a larger societal force.

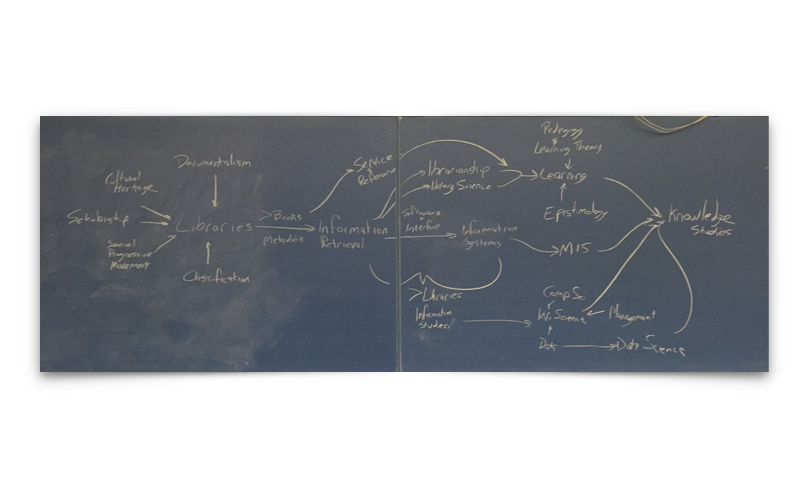

For a long time, we thought that vision was based on information. Why did libraries go from physical owned materials, to physical and digital, owned and licensed resources? Because people needed information, or so the argument went. Books, databases, web pages, it was all part of an information buffet we laid out for our users. And indeed, they were no longer patrons, or even people, they were users. We defined people as what they sought to consume, and we worked very hard to make sure their consumption experience, their user experience, was efficient.

But something happened along this route that increasingly made librarians uncomfortable. Librarians found themselves compared to and aligned with an information industry that did not share our values. Suddenly user experiences in libraries were being compared to user experiences with Google and Facebook. At first as good examples, but librarians began to realize that the industry’s view of people as users, and interactions as experiences was being driven by a quest for data that could be monetized. Technology and data, once seen as neutral, now was being used to drive purchases, and was recreating old inequities. Ultimately making a sale and making meaning in a life are not the same thing, and librarians are increasingly rejecting this narrative. This is not the change we seek to bring to our communities.

It was never stated like this, but it emerged in how librarians started seeing their job and their relation to a community. Suddenly we were talking about third spaces, harking back to Oldenburg’s ground-breaking work. In Europe libraries become the new piazzas, the new town squares. We talked more about democratic participation, learning, and empowerment. Why did libraries move to embrace makerspaces? OK, part was because it was trendy, but the language around their adoption was not on technology and innovation, but empowerment. People, no matter their income or access to industry, could make things.

These ideas of meaning, of community, of providing a place apart from monetizing people as data does not fit into a vision of information. Instead we, as a community, needed to expect more of ourselves and our communities needed to expect more of us. There are thousands upon thousands of information sites available to our communities that are anxious to get our communities’ eyes and their data. We seek their minds and their ways of making meaning.

That is not information – that is knowledge. Our business, in the 4 thousand years of our discipline, has been to make communities smarter, and the lives of community members more meaningful. That starts in their heads – how they see the world. Humans are not just thinking organisms – we are learning organisms. That whole drive to learn and the unknown can be used to create novel and additive experiences to sell product, or it can be used to expand a person’s possibilities.

The librarians of Topeka, the citizens of Ohio, of Toronto, and Edmonton, and British Columbia are examples of how to build knowledge and empowerment. The literacy volunteers in the poor streets of Topeka were not informing users, they were educating people. The homeless of Washing State have come to see their library not as a point of distraction, but as a place to see new possibilities. They seek out the warmth of the building, but also the warmth of human compassion.

And to be clear, what works in Topeka, may not work in Montreal and what works in Plateau-Mont-Royal, may not work in the Borough of NDG. Knowledge is based on the uniqueness of our communities, not some standard that fits all. The days when libraries looked and worked the same across a province, or a country, or a globe are over. The true skill of a librarian is not implementing best practice from abroad, but in understanding their community. Does your college seek to be a top research university or a great teaching institution? Is your neighborhood affluent, or does it need you to serve as a social safety net?

That is a change we can believe in. That is a change that matters. That is a change that is durable.

So, you want to be a change agent? Fine, here’s what you need to know:

You are not neutral. You are less a change agent than an advocate for change. You have a point of view. Listen to your community, learn from your community, and know your professional and personal values. Then act upon them.

You are a facilitator. Yes, librarians can catalog and search, they can manage information, but the great change in our profession is adding the new skill of facilitation to librarians’ tool sets. Your community is your collection and you need to be able to engage that community and get them talking together. And then we must go even further. We must understand that a library is co-owned with the community. Not just overseen, or funded, but in every aspect of operation librarians must team with the community.

Communities are unique and librarians bridge to the global. For too long we viewed libraries as a product of the industrial age, and we sought efficiency and standardizing everything. You could walk into a library in Montréal or Toronto, or Hong Kong and they would have the same general structure. Now, we want community members to walk into a library and see themselves, and their uniqueness. It is the job of the librarians to find the best in Hong Kong and Seattle and adapt it to the local community.

It is time for us to expect more. We should expect more of ourselves. Librarians today don’t simply organize collections of offer programming. We engage communities and advocate for those communities. We empower community members to seek out their best selves and to find meaning. We no longer collect the work of story tellers, we are the story tellers weaving together the narrative of the community from the diverse threads of community members.

We must expect more from our communities. Instead of seeing those that we serve as passive users, we must see our community as a vast array of expertise and aspirations. We need to stop seeking to serve the community, and instead seek to engage that community – to partner with that community. To unleash the powers of that community upon the world.

We must expect more of society. We must work to make our communities more welcoming. We must seek to make our communities more knowledgeable. We must not only be a pace for reflection and investigation, but advocate for more reflection and discussion throughout all of our communities.

As I said in Expect More, a book I wrote and that the librarians of Quebec have now translated into French: Bad libraries build collections, good libraries build services, great libraries build communities. That’s not to say that libraries shouldn’t have good collections, or that libraries shouldn’t have services. Rather it is a call to librarians to focus on the community – the community is your true collection.

We must constantly look to reinvent and understand this profession anew. That’s what a living profession does. We’ve been around for 4 thousand years not because we haven’t changed, but because we have. And we’ve changed not simply because change is always good, but because our communities’ needs have changed. They’ve move from small towns and hamlets to the country side to farms to urban settings. We’ve moved from a slow pace of generational knowledge of monarchies and patriarchies to urban cities and new ideas of democracy. And all along librarians have been part of that transition. We have been advisors of kings, and now are advisors to everyone regardless of rank, regardless of wealth, regardless of race or creed or color. That’s why I am proud to be a librarian. That’s why we need to continue this conversation.

Thank you very much.