Chapter 2: Sick and Tired in Amsterdam

It may seem odd, but in truth I’m not sure when I first knew I was sick. I first became aware something was not right while on a trip to Amsterdam in August of 2012. I was in the Netherlands to speak at the Amsterdam Public Library and Tilburg University.

Excuse me as I take a moment to clarify some misconceptions of professors. Most folks think of professors as people who teach all day. I remember sitting on the campus quad taking a break from writing one summer when a parent approached me with his child. “Excuse me sir, are you a professor here?”

“Yes I am,” I responded.

“Great, it’s summer, so you’re not doing anything and can show us around.” There was no irony in his voice.

A professor at a research university has three jobs: writer, actor, and secretary. Writer in that all of the research we do eventually ends up as an article published somewhere (mostly journals, but sometimes books or other outlets). An actor in that teaching these days is much less about lecturing and more about getting and keeping the attention of students that were raised on Sesame Street and YouTube. And secretary? It is called faculty governance, and it means that you sit in a huge number of meetings and committees discussing everything from should someone get tenure, to planning the annual holiday party.

Now my research is different from that of say a chemist or physicist. I don’t have a lab, and my field of study, library and information science, has a closely aligned group of professionals. That means that part of my job is to see how people and institutions act, while another part is trying to change those same people and intuitions to adopt better ways of working. That means add salesman to the list of my jobs as a professor.

In fact, I spent a good amount of time on the road at conferences speaking and talking with peers. I’m lucky. My area of study is library science, and there are libraries all over the world. I’ve been to Sweden, Italy, China, Austria, Australia, England, Scotland, as well as a fair number of states in the U.S. At one point when my sons were 3 and 6, I calculated that I spent 1/3 of my eldest’s life on the road. After that I cut back, but the Netherlands was still my 6th trip of 2012.

To be honest, I was not that impressed with Amsterdam. The public library was incredible, but the rest of the city was full of expatriate partiers that left the city crowded and dirty. Also, my Irritable Bowel Syndrome seemed to be acting up so I was uncomfortable. I was also wrestling with a bit of a midlife crisis. I had just published a series of books that were well received and I was not sure how to follow that up…or if I should do something different. One great aspect of being a tenured professor is you can pretty much change your job and call it a “shift in research agenda.”

By the time I got home, however, I was feeling sick, had a low-grade fever, and was just tired. As the weeks rolled on I started getting very bad headaches and started losing weight. By October I was sleeping 14 to 16 hours a day and had lost 30 pounds.

Initially my doctor diagnosed me with bronchitis and gave me some hefty antibiotics. Then he added steroids. Nothing. Chest X-Ray for pneumonia. Nothing. I was getting a bit depressed. My mid-life crisis (what am I going to do next) and body woes were not going away. My hands and jaw had also started to tremor. When I showed this to my doctor he called them “conscious tremors; the more you notice them, the more pronounced they become.” Super.

Now I have a great doctor, or as I now have to refer to him, primary care physician (when you have a ton of doctors, each needs their proper title). He refers to me these days as his “humbling patient,” because apparently I remind him how much medicine doesn’t know. My condition was driving him nuts as well. He was sending me for blood tests nearly every week as we tried to figure out what was wrong with me.

Lyme disease – nope

Thyroid – nope

Anemia – nope

Meningitis – nope

Parasite – nope

Kidney disease – nope

Liver – Nope

Nope, nope, nope, nope, nope.

I was not getting better, and we couldn’t figure out why. Then one day, I forgot how to speak.

I came down from bed to watch some TV. I brought up the cable guide and couldn’t make out the words. “Odd,” I thought. So I called the doctor. Here’s how the conversation went:

“Hello, Dr. M’s office?”

“”

“Hello?”

“Words…” It was all I could say.

“Hello?”

I hung up and freaked out. I called my wife:

“Hello?”

“I…can’t…words”

“I’ll be right there.”

Now, I have to take a minute out of the story to point out just what a nerd I am. You see, while I waited for my wife to come home, I pulled out my laptop, opened up my word processor to see if this was just a verbal thing, and wrote the following:

I cannot to plan on studying. I cannot dictate how interests work on in how to I palmons on work how needs make. I cannot trash how to dictating how people busing systems.

Did I mention that I freaked out? I have no clue exactly what I was trying to write, but I think it was along the lines of, “Can I write down the words I want to say?”

It is hard to express exactly how I was feeling at this point. I was terrified, of course. As I’ve said, a HUGE part of my work was based on my ability to speak (lecture, preach, piss and moan). I have to admit, however, I was also a bit intrigued…what could be going on? But to be clear, mostly terrified.

When my wife arrived home, and saw that I couldn’t remember, or at least say, the names of our children, or put a sentence together she whisked me to the emergency room. All along the drive she tried to get me to talk. It was like a bad version of “This is Your Life” mashed up with 20 questions. “What’s my name? What’s your name? When were you born? Where do we live?” By the time we arrived at the doors to the emergency room I’m pretty sure I lost the game, but I was getting a bit better (I finally told her the names of our sons).

The next few hours were a series of monitoring my vitals, sticking my tongue out, and doing stroke tests. Touch your nose; now touch your fingers together. Look up, now right, now left. Do the hokey pokey…no, not really. My words slowly returned after about two hours.

The emergency room led to a night full of MRIs and blood tests. I was finally diagnosed with a Transient Ischemic Attack or TIA. A TIA, I was told, is a mini-stroke that leaves no physical damage. I was prescribed blood thinners, set up with an appointment with a cardiologist and sent home. At least I knew what was wrong with me.

A week before my appointment with the cardiologist, my mother, who came to town to watch me while my wife was away. I was still having bad headaches; I was still sleeping most of the day. Then my mother asked me a question. I was puzzled why, as I answered her, she looked increasingly concerned. I was getting a bit perturbed when she called up my doctor and had me talk to him. I was really upset when she called 911 and had an ambulance come and take me to the emergency room. Apparently, while I thought we were having a nice conversation, we were not having the same conversation. I was making no sense and this time I had no idea. It is terrifying when you can’t make a sentence. It is a hundred fold more so when you don’t know that you can’t make a sentence.

I was taken to an emergency room at a different hospital. This time the doctors skipped the stroke worry and I was handed to neurology that wired me up and gave me an EEG to look at my brain…and another MRI. After a few days in the hospital it was declared that I wasn’t having TIAs, I was having seizures. What’s more, blood thinners would make the problem worse. So I was put on an anti-seizure drug called Keppra and sent home. At least now I knew what was wrong with me.

Now before I jump to the next part of my story, I need to tell you something about Keppra: it’s a deal with the devil. On one hand it does indeed fend off seizures. On the other hand it transformed me into a limp dishtowel with a grumpy disposition. It felt like my brain was slowed down 20%. I hate Keppra. I hate it so much that I once threatened to check myself out of a hospital evaluating me for a potential heart attack if they made me take it again. But for the time being I took it. My kids called me “grumpy daddy.” I was not pleasant to be around.

Worse, I realized that I still didn’t really know what was wrong with me. What caused the seizures? Why did I lose 30 pounds before the seizures showed up? OK, the headaches seemed neurological, but the sleeping? All I knew was that I could speak, my headaches had ended, and I couldn’t drive a car. Not good enough, and not good enough for my primary care doctor who sent me to the Cleveland Clinic to have a look at my brain.

Wired in Cleveland

My wife drove me to Cleveland the day before I was to be admitted to the Cleveland Clinic for a weeklong observation for seizures. We visited the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. We ate at an amazing little Italian place in Cleveland’s Little Italy. The next day we walked down to the Clinic for admission.

How to describe the Cleveland Clinic? Think of the last hospital you were at (other than the Cleveland Clinic obviously). Now throw that away because it is nothing like that. They not only have valet parking, they have a concierge staff that meets you at the door, and directs you to where you need to go. They have a massive atrium with artwork and live classical music. It is the kind of place where you’re sure you are under-dressed even when wearing a hospital supplied gown. It is the kind of place that when they look at your MRI from the Syracuse hospital (I am not making this up) the doctor makes a dismissive sneer and mumbles something about it only be a 1 Tesla machine.

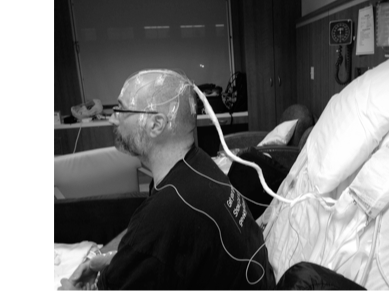

I went to the Cleveland Clinic for a five day EEG test. This involved first lying face down in a bed as a technician glued 24 electrodes to my head (the technicians fought to get me because my head was nice and shaved). The electrodes were connected to a long cord that disappeared into the wall behind me. The first ponytail I’ve had in my life couldn’t be disconnected, except by a nurse when I had to go to the bathroom. There is a special kind of pressure trying to go the bathroom with a nurse waiting outside your door holding your wire bundle.

For the next 5 days I lay in a bed while being watched by an infrared video camera. The doctors watched me day and night to see if there was a disturbance in the EEG (like the force) and how it physically manifested itself.

At the end of the week they declared me healthy, no epilepsy, no seizures, stop taking Keppra and go home. When I asked what had caused all my symptoms their answer was, and I quote, “We don’t have a time machine to go back and find out,” and, “There are a lot of things that can make the brain act out.” So now I had no idea what was wrong with me, if it was still wrong. If only they had looked 6 inches lower than my skull, they might have seen the cancer growing in my chest.